Held March 20-22, this year’s Intercollegiate Iron Pour offered School of Art students a rare chance to explore Pittsburgh’s legacy through contemporary sculpture.

In art, as in most things, failure often forges the strongest results. “With this class, there’s a lot of failure, and I think that’s a good thing,” said Carnegie Mellon School of Art Professor Britt Ransom. Her Intermediate Mold Making students spent the semester experimenting with an array of techniques, which they put to the test at the 2025 Intercollegiate Iron Pour — a three-day workshop at Pittsburgh’s historic Carrie Blast Furnaces.

Now in its second year, the Intercollegiate Iron Pour — hosted by Rivers of Steel — offers students the opportunity to directly engage with the materials and methods of Pittsburgh’s industrial past. Guided by Ed Parrish, Jr., Rivers of Steel’s Metal Arts Coordinator & Furnace Master, students spent two days crafting molds in resin-bonded sand from wax patterns, culminating on the final day when the molten iron was finally poured, a meticulous process requiring precision and teamwork. CMU students were joined by peers from the University of Notre Dame, Alfred University, Seton Hill University, and the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

“It’s really one of the most rewarding parts of the work we’re doing, providing access to students that maybe would never see this, learn new processes, or have access to materials and new ways of working,” said Parrish. “That’s how I was introduced to this as a student, and it’s been a lifelong pursuit, so it’s really great to be able to share that with other creative folks.”

Mold Making is a highly technical studio course, where students learn to cast objects in wax using one-part and two-part molds made of silicone or rubber. By the end of the semester, students will have covered six distinct types of molds, including 3D printing. Students’ engagement in the class laid the groundwork for their participation in the workshop, dedicating intensive full days outside of class time to see their work transformed into metal. Part of the aim is to illuminate how everyday objects — or even iconic ones, like the Academy Awards’ Oscar statue — are made. “A big part of the conversation in class is about looking at objects and thinking about how it goes from wax to plaster to resin,” said Ransom. “The next time you go out in the world and see a wrought iron fence, consider that a lot of molds and positives for things like that started here in Pittsburgh.”

The Carrie Blast Furnaces complex was built in the 1880s as part of Homestead Steel Works and designated a National Historic Landmark in 2006. The site sat empty after shutting down between 1978 and 1984, after which it was rescued by the citizen-organized group that would eventually become Rivers of Steel, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the region’s steelmaking legacy.

Though iron casting communities remain — like Sculpture Trails in Indiana and Sloss Furnaces in Alabama — most surviving foundries today are based in academia, making Carrie Blast Furnaces a rare example of pre-World War II iron-making technology. “Technologies change and progress,” explained Parrish. “Pittsburgh is a technology hub in that we’re now dealing with medical and computers and robots — but, back in the day, steel was the high-tech of that era.”

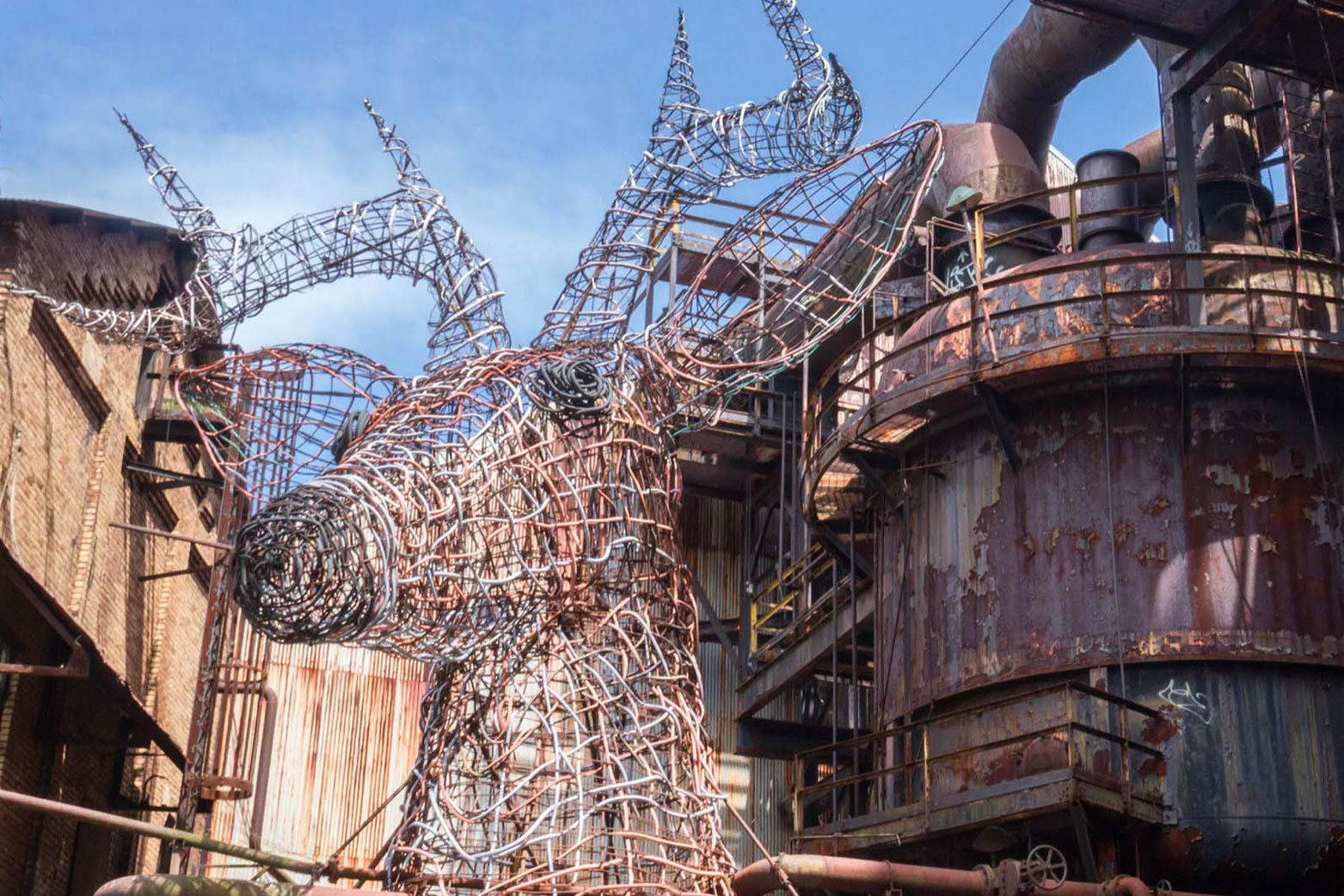

Today, Rivers of Steel’s Metal Arts programming has transformed the Carrie Blast Furnaces into a hub for creative exploration, where artists have long intervened in the site with graffiti and guerilla art, including the Rankin Deer, a 45-foot buck head sculpture made from found steel, copper, and rubber. The 2015 project, Iron Garden, was a collaboration with master gardeners Addy Smith-Reiman and Joshua Reiman. Most recently, the Andy Warhol Museum celebrated its 30th Anniversary Gala at the Furnaces. Even small details are a testament to the site’s enduring artistic legacy, like the furnace used for the Intercollegiate Iron Pour, affectionately nicknamed “Bumblepig” for a whimsical bumblebee-pig illustration on its surface.

For junior Morgan (Mo) Nash, who grew up in Pittsburgh, the opportunity to create artwork at the Furnaces held personal significance. “My cousins live right across the river, and a lot of my family still works in the steel mill that’s further down the river,” they said. “So I was really excited to go, because it’s my ancestry.” Nash chose to mold a series of Eat’n Park cookies, a nostalgic symbol of Pittsburgh’s culinary culture. Second-year MFA student Naomi Chambers also made molds of cookies in class, which are currently on view at the 1st and 2nd Year MFA Exhibition at SPACE Gallery. Other students cast a range of objects — from mirrors and tiny scissors to ramen and a bag of chips. “What’s been really fun is trying to respond to the various things they’re bringing into class,” said Ransom. “It’s about teaching each person, individually, how to think through an object: how big it is, how materials travel in and out, how air gets trapped. It’s really been an interesting challenge.”

Outside of the pour, there’s a broader recent history of the School of Art community exploring the possibilities of working with Rivers of Steel. Third-year MFA student Frankmarlin produced work for their thesis show, currently on view at The Andy Warhol Museum. Sophomore Priyanka Acharya, who joined the workshop as a guest from another School of Art course, Digital Fabrication, had already visited the furnaces for a bladesmithing workshop as a member of CMU’s Forge Club. “I’m really interested in metals, and anything I can do at Rivers of Steel, I’m like, sign me up.”

The Mold Making class also happened to coincide with a visit by sculptor Kelly Akashi — who often works at the intersection of bronze and glass — as part of the School of Art’s Visiting Artist Lecture Series. Heading into the workshop, “I was thinking about how she was talking about her ritualistic approach to her practice,” Nash shared. “It reminded me to be mindful of each step of the process, and how my body was so involved with it.”

Participating in this year’s Intercollegiate Iron Pour is just the beginning of an exploration that will continue to shape students’ artistic practices. For Nash, that means further incorporating metals into a sculpture practice that is highly tactile and interactive. For Acharya, it’s a deepening exploration of small metals jewelry casting. For sophomore Veronika Eber, who had planned to cast a piece made at the Pittsburgh Glass Center until it broke during mold prep, it means learning to embrace failure as part of the process.

“It’s disappointing to work on something for a week, and then it doesn’t necessarily always work out the first time,” said Ransom. “But I watched them redo it the second time, and it’s 10 times faster. They’ve really started to understand the object.”