As a kid, D. Fox Harrell spent his summers computer programming, but he also enjoyed writing poetry, making artwork, reading fiction, and playing in a punk rock band with his friends. Even from an early age, Harrell knew that each of his eclectic interests was worth pursuing, so he began envisioning how to combine them all through computing and the arts.

Today, Dr. Harrell continues to combine seemingly disparate fields—such computer science, philosophy, psychology, cultural studies, media arts, and more—to explore the relationship between imagination and computation. In his research, theoretical writing, and computational practice, Dr. Harrell is at the forefront of a new way of thinking about computation. His work centers the ethical development and application of computing and artificial intelligence research to create systems that are engaging, dynamic, and foster positive impact on critical social issues.

Dr. Harrell is Professor of Digital Media & Artificial Intelligence in the Comparative Media Studies Program and Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) at MIT. He is also the Founding Director, Studio Head, and Principal Investigator of MIT’s Center for Advanced Virtuality, a studio, laboratory, and research center that pioneers innovative experiences that use technologies such as virtual reality, augmented reality, synthetic media, and more.

Dr. Harrell’s undergraduate experience at CMU was early proof that crossing disciplinary fields could yield new ways of thinking about and creating computational experiences. After seeing a brochure for CMU’s Pre-College Program at a friend’s house, he applied and was admitted to the music program on the basis of a demo tape (he only played bass by ear). During his summer at CMU, he collected brochures for as many university programs as he could find, and he met with Wilfred Sieg, then the department head for Logic and Computation. He decided to come to CMU as an undergraduate, earning a BFA degree with a focus on electronic and time-based media, a BS in Logic and Computation, and a minor in computer science.

From the first-year rigors of a drawing class taught by Professor Herb Olds and concept studio class with Professor Andrew Johnson to a senior year animation course with Professor James Duesing, Dr. Harrell said that several of his courses had a transformative impact on his future career. One course that particularly stands out is an art theory course taught by Professor Steve Kurtz. “The way the course integrated the philosophy of art, cultural studies, critical theory and more brought together my interest in work for a societal impact with my interest in art,” he said.

At CMU, Dr. Harrell also honed his interest in AI and found that bringing together the arts and AI opened up new possibilities for storytelling. For instance, he said he found Professor Manuela Veloso’s AI course and Professor Tom Mitchell’s Machine Learning courses were illuminating—and Professor Jeremy Avigad’s course on logic and computability offered a brilliant approach to mathematical formalization. As opposed to a static medium, AI enables creators to reconfigure stories in terms of social perspective, cultural metaphor, values, styles and more, allowing for the possibility of creating flexible experiences that address a wide variety of viewpoints.

According to Dr. Harrell, many current forms of AI, largely developed for commercial use, do not yet integrate flexibility and responsiveness to diverse needs. For example, a recommender system is designed only with a utilitarian aim in mind: to give people exactly what they want. While these systems originate from the idea of “personalization,” they ultimately build consensus through categorizing people and creating self-reinforcing loops. People who fall outside of the group consensus, i.e., those with more idiosyncratic tastes, become left out. Many of the same biases that exist in the physical world are too often replicated, or even amplified, by this type of system.

Dr. Harrell designs systems that are more akin to how an improvisational performer might interact with an audience. Rather than deliver exactly want a person might want, the system can also deliver what a person might need. This is where art plays a crucial role in his work: art has a special ability to “provoke, challenge, offer new ways to think, spark imagination, and more,” he said. To accomplish this technically, Dr. Harrell invented his own platform, called Chimera that he and his team have been refining ever since.

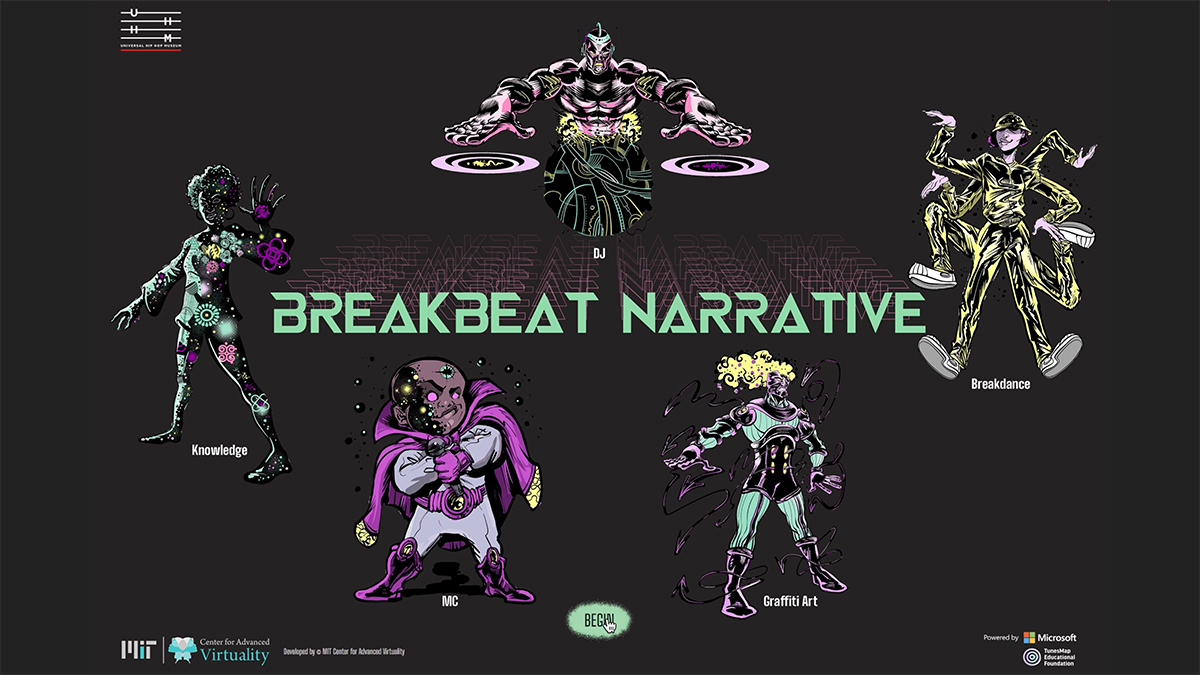

One example of how a system might act in a more improvisational way is Dr. Harrell’s project “The [R]Evolution of Hip Hop Breakbeat Narratives,” a collaboration between the MIT Center for Advanced Virtuality, Microsoft, and the Universal Hip Hop Museum. The project is a kiosk-based system that uses fictional characters—that he created in collaboration with graphic novelists John Jennings and Stacey Robinson—to go beyond the basics in order to tell the complex histories of Hip Hop and its socio-cultural impact. Visitors enter into a conversation with these fictional characters who learn about their musical tastes and interests via a conversation in order to tailor a narrative about Hip Hop history specifically for them.

“A lot of time, people feel that AI systems have to operate 100 percent autonomously,” Dr. Harrell said, “but I’m interested in ways that AI systems can operate with people, and in the way that systems might do the unexpected, but in a manner constrained by careful ways of formalizing semantics.” That is, his approach does not produce random ambiguity, he explained, instead producing “improvisationally-generated content with coherent meaning to provoke thought and ideally positive social change.”

In his book 2013 book Phantasmal Media: An Approach to Imagination, Computation and Expression, Dr. Harrell elaborates on the expressive potential of computation. This unique medium can construct and reveal phantasms, “a particular pervasive kind of imagination, one that encompasses cognitive phenomena including sense of self, metaphor, social categorization, narrative, and poetic thinking.” Phantasms can be both oppressive, creating and reinforcing biases, or empowering. Therefore, it is up to creators to be conscious of this unique power and work to create empowering phantasms.

“The Enemy,” a project directed by the war photographer Karim Ben Khelifa that Dr. Harrell collaborated on as the Human-Computer Interaction Producer, challenges visitors to experience and look at war in a new way. In an era where people are increasingly desensitized to images of violence, “The Enemy” is a virtual reality experience that puts visitors in conversation with combatants on both sides of conflicts. The system reads the user’s body language and other cues to create unique experiences, both in the conversation with combatants and in the physical surrounding. For example, if the user is inattentive, the skylights will darken as if on a cloudy day. In the end, the experience seeks to “reveal humanity and show how dehumanization is a precondition for war,” he said.

Dr. Harrell’s work also goes beyond computation. While he has been leading his center’s research in exploring computationally-supported roleplaying to support perspective transformation, he has written for roleplaying in popular culture gaming to do the same. Last year, he wrote an adventure called The Nightsea’s Succor, which was published in the book Journey’s Through the Radiant Citadel. This book is the first Dungeons and Dragons book that is entirely based in non-Western settings, and Dr. Harrell’s story in particular is based on cultures from Africa and the African diaspora. The book was recently nominated for a 2023 Nebula Award, given by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association.

No matter what medium he’s working in, Dr. Harrell seeks to create works that cut across academic settings, fine art venues, popular culture and more. “There is a research side and there is an impact side,” he says, “and it’s really important to me the works coming out of [the Center for Advanced Virtuality] have a real impact.”

Portrait image: Bryce Vickmark for MIT News 4/1/14