The Whitney Museum of American Art acquired the artwork “Koupe Tet, Boule Kay” by School of Art senior Steven for its permanent collection.

The work began as a way for Montinar to improve his drawing skills during quarantine, he said. Though he had never used Adobe Illustrator before—and lacked any sort of drawing tablet that most artists consider essential to working in the software—over the course of two weeks he created the digital illustration.

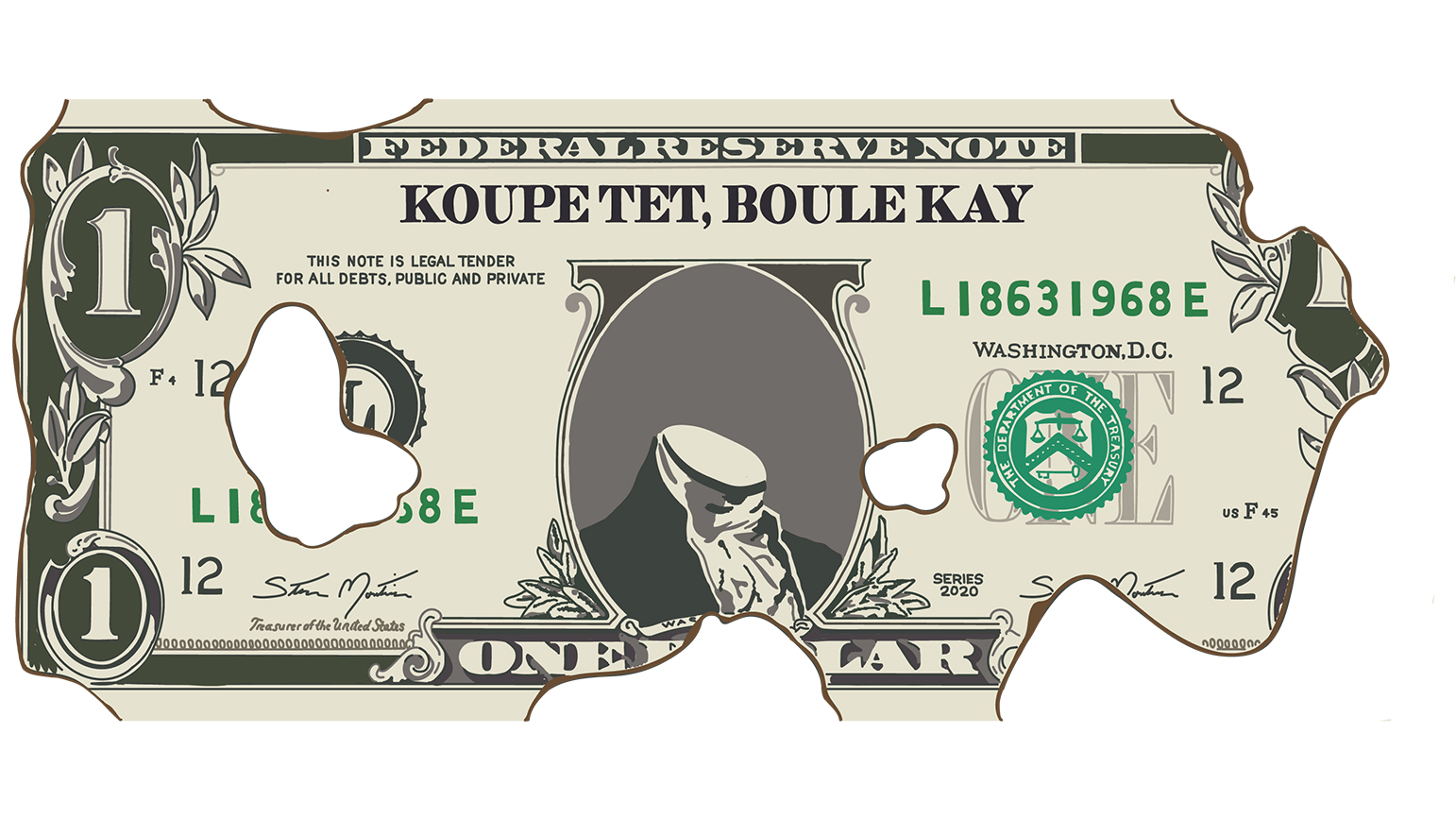

“Koupe Tet, Boule Kay” shows a U.S. dollar bill with burn marks around the edges, a decapitated bust in the center, and the titular phrase replacing the text “United States of America” across the top of the bill. The phrase, which translates to “cut heads, burn houses,” was to a rallying cry of the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), the largest and most successful slave rebellion in the Western Hemisphere. The Revolution gained Haiti independence from France and led to the creation of the first country founded by formerly enslaved people.

For his work, Montinar said he focused on how the phrase “Koupe Tet, Boule Kay” has meaning today, especially in the context of the Black Lives Matter movement. Even though “you’re crossing a cultural standpoint and also a time period difference,” he said, “I knew this phrase and history was still relevant. I wanted to see how could I reinvent the imagery to be visually relevant as well.”

Montinar said he chose the dollar bill because in a capitalist society like the United States “the head is money.” In the struggle for justice, he said, it is easy for those in power to maintain the status quo.

“When you attack someone’s pocket, they may not listen, but they will at least try to see what’s going on,” he said.

Elements of the artwork also allude to important dates in U.S. history and the current movement for social justice. The serial number contains the dates 1863, the year of the Emancipation Proclamation, and 1968, the year of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination. Other letters and numbers on the bill—“F 12” and “US F 45”—point to the movement fighting police brutality and a rejection of the Donald Trump presidency.

Growing up a first-generation Haitian American, Montinar said he heard the phrase “Koupe Tet, Boule Kay” before, but had to do additional research to understand its significance for this project. As a kid, he said, his parents encouraged him to assimilate into dominant American culture rather than learn about his cultural background and identity, a fact that informs his artistic practice. His current artwork both examines the everyday oppression of Black Americans and pays tribute to the contributions of Black society.

The work was set to be part of the Whitney Museum exhibition “Collective Action: Artist Interventions in a Time of Change,” which was cancelled shortly after it was announced. The exhibition would have included prints, photographs, posters, and digital files created this year in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Following the exhibition announcement, the museum received criticism from several artists to be included in “Collective Action.” These artists objected to an institution with considerable financial resources acquiring artwork at discount prices through fundraisers, especially given the historical lack of investment in Black artists by major museums. Some artists also criticized the museum for only notifying them that they were included in the show after it was announced and less than a month before it opened.

Some of the work that the Whitney acquired, like Montinar’s contribution, were distributed online for free to use in protests or display in windows. “Koupe, Tet, Boule Kay” is still available as a free download through Printed Matter, a nonprofit focusing on artists’ books and publications.

“I’m a senior in college right now, so hearing that the Whitney wanted to exhibit me was huge,” Montinar told the online art publication Hyperallergic following the cancelation of “Collective Action.” “A lot of what I’m doing right now is for exposure, because I’m still building a portfolio.”

Reading other artists’ criticisms on social media caused him to reflect further on his work and its inclusion in the exhibition. “With the type of work I make, I can’t just not stand in solidarity with the artists and the people who look like me, that’s who I make my works for,” he told Hyperallergic. “It’s important for me to stand with people. A lot of movements, especially the BLM movement, come from people not being heard.”