On the Ground is a series featuring research by graduate and undergraduate School of Art students at Carnegie Mellon University that offers a glimpse into the particular contexts, processes, and methods of inquiry that drive their work beyond the confines of the studio. This installment comes from Katie Rose Pipkin, a 2018 Masters of Fine Arts candidate whose is a drawing and language artist from the woods outside of Austin, TX.

The Game Developers Conference, or GDC, is an annual industry event ‘focusing on learning, inspiration, and networking’. Each year, some 26,000-odd game industry professionals attend talks, workshops, sales pitches, rewards shows, and parties. Hosted in San Francisco’s rather ostentatious Moscone Center at Yerba Buena Gardens (and with each badge valued at some $2000), it is not the sort of place I tend towards naturally.

I was invited to show a work I produced last year for the Triennale Design Museum of Milan, as part of their game collection (curated by Santa Ragione). The collection is available for free on mobile and Steam, and has work from Tale of Tales, Cardboard Computer, Pol Clarissou, and Mario von Rickenbach & Christian Etter. My part (a walking simulator set in an endless, generative greenhouse made of botanical illustrations), is called The Worm Room.

The collection was hosted by Mild Rumpus, honorary home of the GDC-weird. Here, 20-odd experimental projects face inward, forming a kind of fort where indie developers and queer folks seem to gather and catch, although the odd-UI designer or project lead will also wander through. It is easily the least-corporate space of GDC; nobody is trying to attract publishers, nothing is up for an award. The other work is complicated and strange, and I am grateful for the good company.

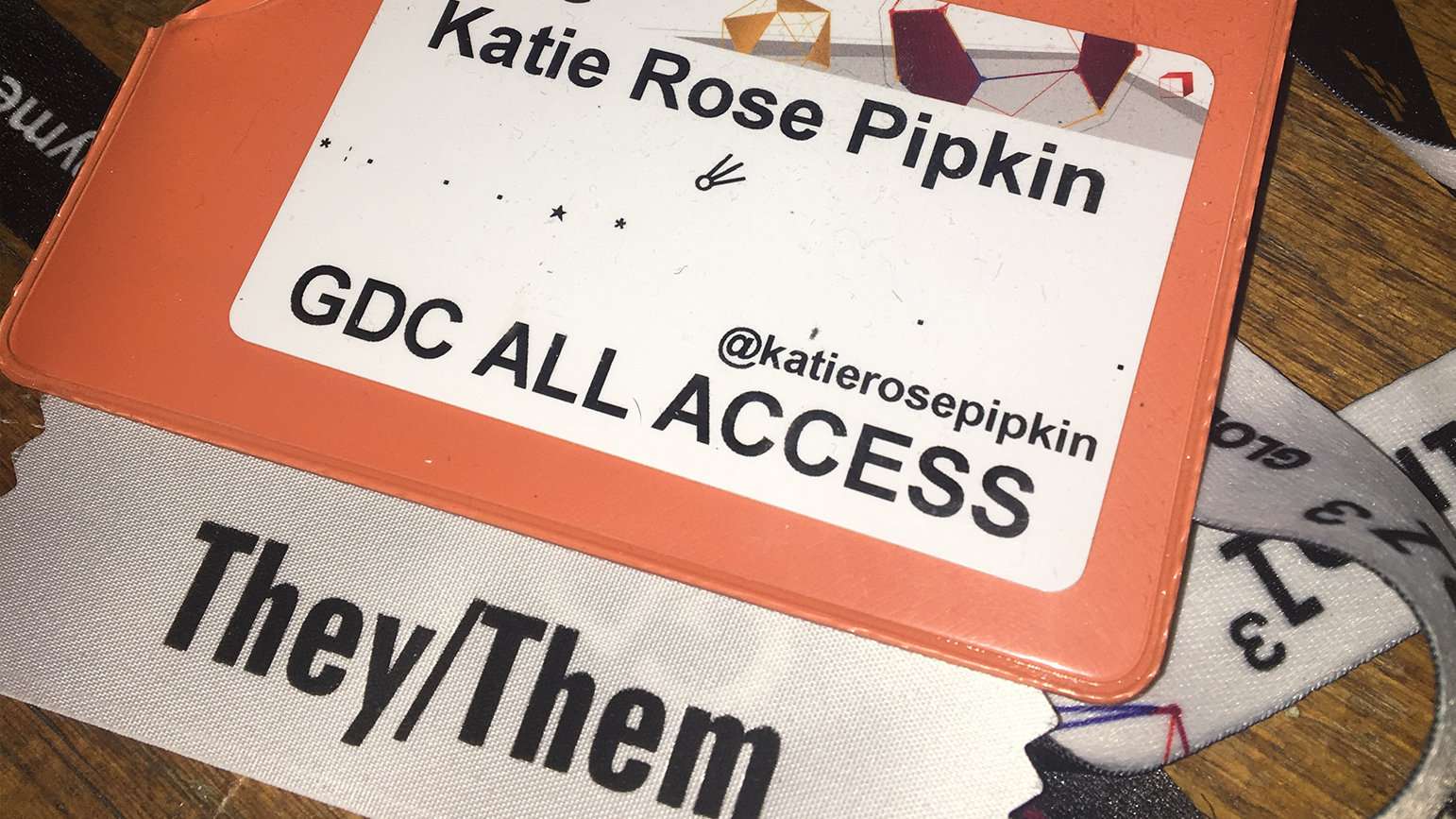

In fairness, I may be slightly over-selling the corporate nature of the event. Like game development at large, the monolith of AAA games is broken up by artists and independent developers. The conference itself makes some effort at this. The Experimental Gameplay Workshop hosts games with odd physical controllers (vacuums, popsicles, etc), and the entrants in the Independent Games Festival are always remarkable. Optional pronoun tags come with each registered badge. One is given the option of He, She, They, and inexplicably, Steve Gaynor (a minor celebrity who worked on BioShock 2, which is a joke that would seem less innocuous if I had seen anyone but Steve Gaynor sporting one).

But effort or not, the presiding culture is one of money, and everyone is hustling. My 3rd day at the conference, I convince a friend to take the train up from LA to join me. She does not work in the industry, but I sell her on a visit with a promise of a free pass and ‘one of the weirdest days of her life’. It doesn’t disappoint. We wander the expo floor, which spans a few city blocks underground and is thoroughly separated from the experimental corner where my work is living. Here, 3-story booths sponsored by Facebook and Amazon and Google tower over everything, made to look like tree forts or old motels or medieval castles. Inside, employees make espresso and set-up meetings between the high-powered, while visitors lounge around on custom cube seating. You can tell if the company is important by checking if they are demoing anything. For the 3-story booths, who sell nothing but their names, GDC is almost always just a show of wealth.

Spreading outward are the less-than-giants; Mozilla, Dropbox, Wwise, Unity. They give out buttons and pencils, and chat about their new APIs. Some bake fresh cookies. After these is a sea of folding tables, divided cheaply by fabric barriers. These are the heart of the thing; table after table of third-party add-ons and proprietary controllers and middle-ware solutions to grass growth or dragon-eye modeling. These are workers in contemporary craft, and they are excellent at what they do.

In what might not be an entirely fair move, I’ve worn sharp business, and displayed my All Access pass prominently. Unlike most crowds, I don’t look too young to be important here. It is San Francisco start-up culture, and I want the hard sell.

This year, I’ve fixated on the variety of VR glove controllers on display, each vying to solve the problem of space-tracking and haptic feedback in virtual reality. I search them out and try each one on to take a photo. Aesthetically, the images make an odd group- they have a feeling of severed hands. I think it is because they are so clearly functional rather than decorative, but they also serve as a link to another hand, a virtual hand. I want to pick one up by the thumb and wiggle it like a worm and watch the images on the screen react, but I am concerned with my tenuous business-suit status.

I have a long conversation with the person at Speedtree, the software solution for realistic foliage. She explains that they do most of their bark scans in a national botanical garden near Washington, D.C., but sometimes specific trees require travel. She says that just last year they had to send a photographer to East Asia for some rain forest varietals, and that it is hard work but rewarding. She even shows me how she builds stumps (it is all in the shelf fungus, if she is to be believed).

I have to cut off the conversation to rescue my friend from an overzealous engineer who is explaining emotion modeling.

The work is remarkable. Dense, studied, cared-for, these are the irrelevant backgrounds to the new digital world. Each folding table sells a detail so minor that it is not worth branding as in-house, so instead the same fire technology is duplicated from Grand Theft Auto to Skyrim to Trolls 2. These fragments are designed to be realistic but mutable; believable but not stand-out; natural, not made. They fail at this, of course. Each one has a hand to it- these are small companies, sometimes just one person, and it is impossible to keep one’s individual look out. Maybe this is why there are so many tables selling trees.

It is exhausting being underground among the discount tables, pretending my interest is financially backed. I don’t know how anyone manages to sell for the week- I can barely muster 5 hours. I retreat to the ease of my own settled work, which requires no further funding this year. But I am taken as always by the space- the shattering of capital across prototype, the start-ups that won’t survive until next year, the hand-sewn gloves that will never reach production. I also care for the successful; the $50,000 tree package that requires a photographer to fly to the other side of the world to capture the perfect bark texture. The pieces will soon assemble into first-person-shooters and new home consoles and cloud-storage solutions. But I am grateful to have been there when the pieces were singular. I met the shelf-fungus stump first, when that was all it was.

Katie Rose Pipkin holds a BFA from University of Texas at Austin, and has shown nationally and internationally at The Design Museum of London, the Texas Biennial, XXI Triennale of Milan, The Victoria & Albert Museum, and others. They produce printed material as books, chapbooks, and zines, as well as digital work in software, bots, and games. They also make drawings by hand, on paper.