Before Kelly Akashi’s March 18 lecture at CMU, Professor Isla Hansen explores the artist’s deep engagement with material transformation and the fleeting nature of time.

By Professor Isla Hansen

In Kelly Akashi’s sculpture Life Forms (2023), a cast bronze hand, presumably the artist’s, reaches into a morphing bubble of Iris Amber glass. This singular piece is emblematic of much of Akashi’s work. It combines things both seemingly fragile yet hard, freezing them in a precious moment in which something human gently interacts with something perhaps more representative of nature. Like an illusion, or a photograph, the sculpture captures an impossible moment just before a bubble is popped, or an egg yolk broken, seemingly defying gravity and the material physical properties we associate with living on Earth.

And yet, at the same time, Akashi highlights the material properties of her chosen media — qualities that any skilled artist or craftsperson, deeply invested in the process of making, would strive to capture: the detail of every tiny wrinkle line in her hand, achieved through the lost-wax bronze casting process; the magical blend of protective amber colored glass with iris, a unique iridescent clear glass, combined through a delicate hand-blowing process, blown with the artist’s own breath and labor.

The artist’s hand is apparent in the work in more ways than one. It’s as if the piece tells the story of its own making, a labor of both impossibly hard work, but also curiosity, as evident in the gentle touch of the hand. Beyond creating a work about the creation of sculpture itself, Akashi’s work stands, better balanced than it seems, for a greater relationship between our hands and the matters both material and immaterial they reach for and manipulate in the world.

Akashi describes her work in relation to the Japanese idiom mono no aware, which the artist explains as “a wistful awareness of impermanence – the ‘pathos of things.’” Looking at more of Akashi’s works, the way she draws attention to things that should be ephemeral becomes clear. She reminds us of the entanglement of tree branches as they grow, evokes consciousness of our own aging bodies, compares it to the decay of sagging onion skin, shows us the way a candle melts next to a similarly melting hand, or the way flowers wilt and die. But in this case, the flowers remain crystalized in glass, don’t they?

After looking at and thinking about Akashi’s work for some time, I thought about that legendary property of glass that I have conveniently believed for some years: that glass is liquid, slowly, but constantly, moving. I did what anyone tasked with putting words to (virtual) paper should do and I fact-checked. While glass does share some properties with liquids, it turns out that some scientists in 2017 advanced ideas behind glass transition theory, showing that the viscous flow of glass is practically unobservable on a human time scale. Next to the lifespans of Akashi’s chosen materials, it is ours that are short lived and impermanent.

Debunking the liquid glass myth makes me a bit sad. I’d planned to anchor writing about Akashi’s work on the notion that the precious, solid-seeming materials Akashi is using — that most galleries and museums associate with being “archival,” and therefore more valuable — are in actuality all melting! The sculptures themselves turning out to be more ephemeral would give you the perfect bittersweet sense of mono no aware, and perhaps give you a sense of critique of the material conditions of the art market the works exist in. But I think understanding more about the truth, or our human unknowing of the great material truths behind Akashi’s media, makes the work more meaningful to me.

The truth is that we humans don’t understand why glass flows at all; scientists can’t definitively classify glass as a liquid or a solid, and recently some question whether it may even represent a newly definable, separate state of matter. It resists categorization! It seems exciting! Akashi’s work makes me think again and again about that human urge to science — to ask questions about the natural world around us, and about our own bodies, and to try to find the answers. Is there anything that evokes feelings of mono no aware more than our failed attempts to understand everything about the universe? Perhaps it is beautiful that we will never know all the mysteries, that things pass before they can be fully understood.

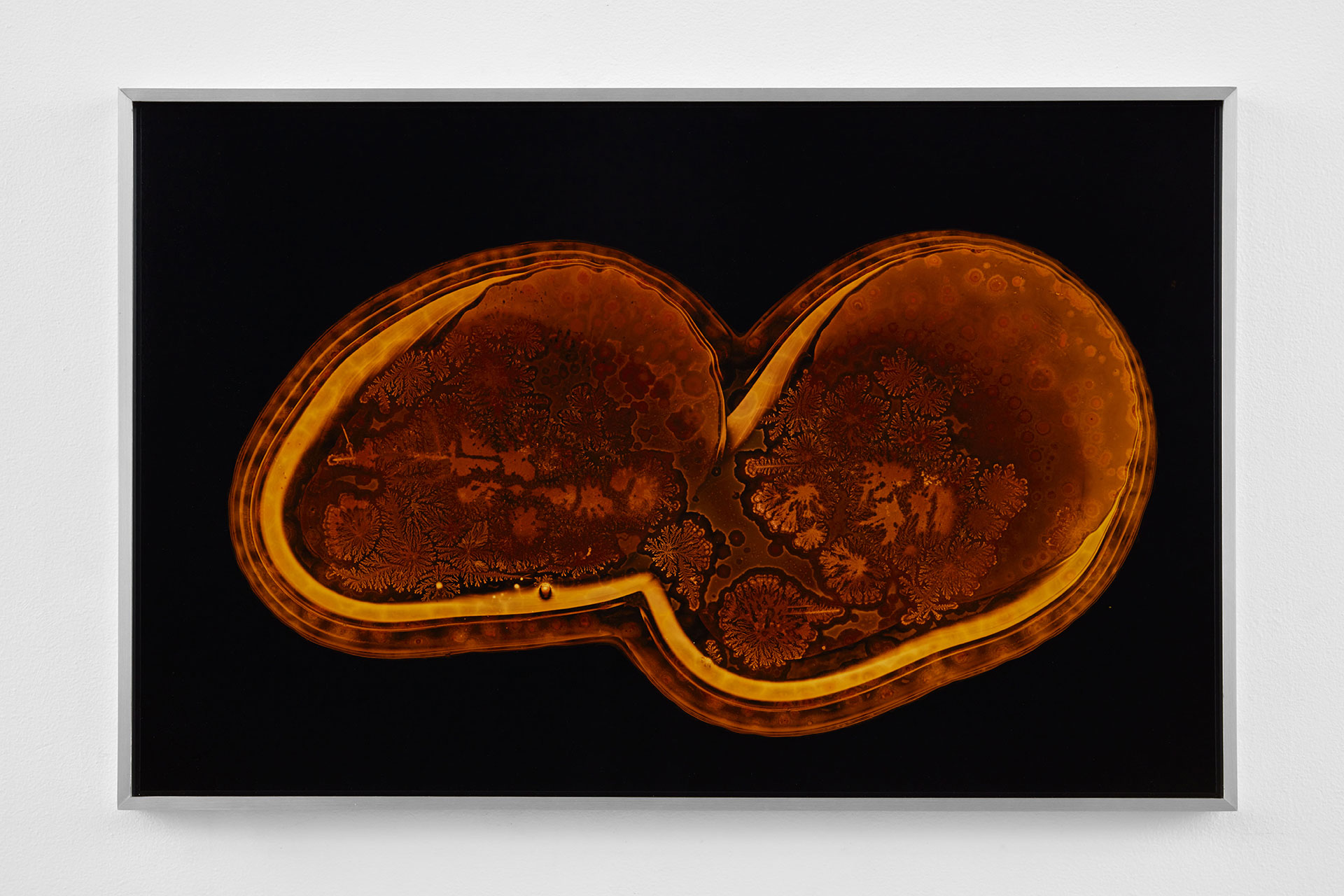

Another of Akashi’s works, Fractured Thigh-Tooth (2022), is made of carved and polished onyx. Onyx is said to be formed over thousands of years from the dripping of water in caves, when minerals of calcite crystalize into stalactites and stalagmites. It’s another example of a process by which something seemingly liquid turns to into something seemingly solid. Akashi’s carving and polishing of the stone is like a collaboration on top of processes centuries in the making. The liquid-to-solid transformation actually defines many of the materials that Akashi uses under mostly very hot conditions, including wax, bronze, glass, borosilicate, silicone, even steel. Through these processes, Akashi is witness to remarkable changes in the material conditions and properties of matter. It is in the sculptures themselves, but even more so in the work Akashi does, that the ideas of things being in continual flux really plays out.

Mono no aware is often linked to the Buddhist idea of annica, which quite literally translated from Pali to English means not everlasting, not eternal, or the opposite of unchanging. In Buddhism, the stability we project onto the world or onto ourselves is an entirely constructed reliability. Somehow, though Akashi’s work is made from some of the most seemingly lasting, hard, and precious materials, it argues that the conditions of the world are in a continual state of change. This position is hard to disagree with in our current moment, as politically, climatically, and technologically, things do seem in constant motion, moving forward and backward all at once.

Akashi’s work is somehow simultaneously timeless and timely. That her work can communicate all this in our time through such dedication to processes and crafts that are not new is quite impressive to me. It reminds me of one of the things that art can offer to science, and therefore to the world. There are things that people who work with their hands know about the materials they work with. Especially laborers, tradespeople, craftspeople, and artists who work with the same materials over and over again. It’s a physical knowledge that doesn’t necessarily begin with a question, and doesn’t necessarily end with an answer. And that knowledge sometimes cannot be conveyed with words, but must be shown as a physical manifestation of this knowledge, a series of wordless gestures.

To me, Akashi’s work is about curiosity and knowledge. Though the work exemplifies some of what Akashi knows about some of the materials the world contains, the work is also about all that we don’t know as humans, all that is inconceivable, all that we can only touch briefly before it passes from this world, or we do.

Author’s Note: None of this was written with AI!

Some sources used to write this essay, or to look at in conjunction with it:

Lisson Gallery

“Kelly Akashi. Converging Figures” Fondazione Furia

“Viscous flow of medieval cathedral glass” Journal of the American Ceramics Society

“Is glass a state of matter?” Cornell University

“The surprising scientific weirdness of glass” Vox

“The Context of Impermanence” Barre Center for Buddhist Studies

Join us on March 18 at 5:30 pm in Kresge Theatre to hear Kelly Akashi’s lecture. Full details here.