Appalachian “Coal Country” is aptly named. With its railroads and coal tipples, its mountains blasted in search of subterranean treasures, museums filled with artifacts of hard and dangerous labor below ground, it has been profoundly shaped by extractive industry. Often regarded by outsiders as a backwater, it is the site of centuries of conflict, where poverty (too often figured as shameful personal failing), exploitation, and erasure are compounded over generations, and pitched against histories of racism, solidarity, and collective action. Between Great Depression era poverty pictures, the violent and retrograde hillbilly of popular imagination, and the confused rhetoric which today describes a “forgotten tribe” of beleaguered white hill people inhabiting an unfamiliar “Other America,” when I set out on this trip I couldn’t help but feel I was going to a mythical land, or at least, one deeply mythologized. My interest in its history—how it is variously preserved, buried, or put to use—was rightly met by the people I spoke to with some skepticism. As Elizabeth Barrett puts it in her 1997 documentary Stranger with a Camera, my visit was prefaced by a long history of outsiders mining images, the way the companies mine coal. What is at stake in all this rhetoric, a theme I encountered over and over again on my short visit, is the question of who gets to be the author and subject of American History, and who the proper object of our sympathies is.

Blair Mountain, site of the culminating battle of the Mine Wars, provides a startling example. The Battle of Blair Mountain was one of the largest uprisings in US history since the Civil War, where some 10,000 coal miners fought 3,000 strike breakers during their attempt to unionize West Virginia’s southern coalfields. It ended when the US army intervened by presidential order. This was the first and only time the federal government planned to drop bombs from airplanes onto US citizens. Although the planes were turned back by a storm over the mountains, the miners were forced to retreat when federal troops arrived.

Now it is owned by subsidiaries of Massey Energy and Arch Coal, two of the largest coal companies in the country. This lent my visit to Blair Mountain a certain urgency: it will soon have its top removed, destroying any remaining artifacts from this little known conflict. A gate blocked passage to the summit, I called the nearby office of Mountain Laurel Coal to ask permission to continue. I was told they couldn’t give me permission without going to corporate, but that it should be safe. Not only would nobody bother me, I was told, but there was really not much to see anyways. Others had come and gone, activists, researchers, and little had come of it.

At the top, where the road ends in kind of a cul-de-sac clearing, there was little but trees and snow. I felt pretty foolish—I wasn’t equipped to do proper archaeology, didn’t know where to go or what to look for. I took a few photos, evidence that I had set foot on the mountain before it was gone, and got back on the road.

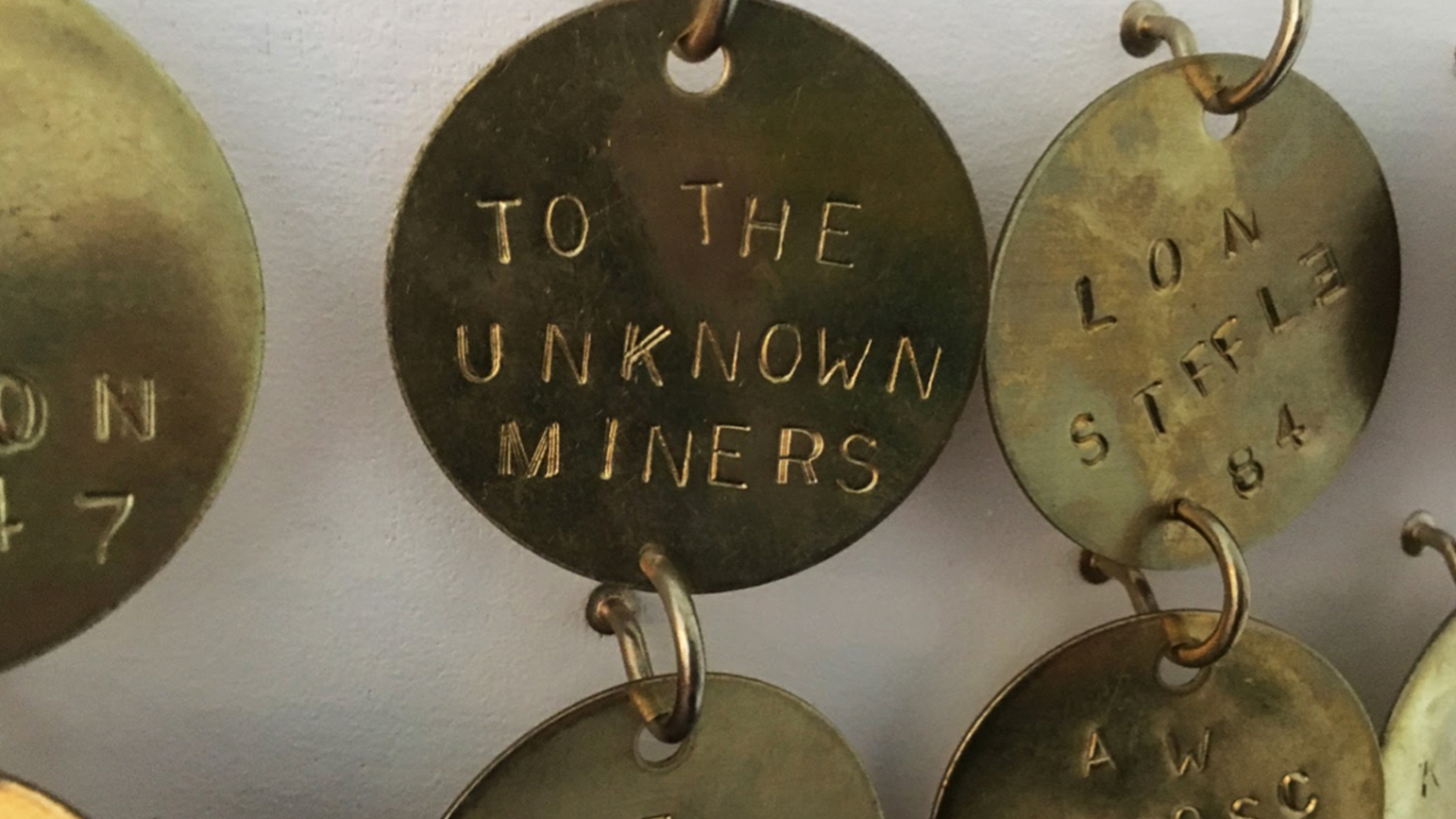

I stayed a few nights near the site of the Matewan Massacre, a shootout between unionized miners and Baldwin-Felts agents that prefigured the battle of Blair Mountain. The West Virginia Mine Wars Museum, a project of Pittsburgh based artist Shaun Slifer, occupies one of the storefronts in Matewan, facing where the shootout took place. There I saw vitrines filled with rusted coal scrip, an authentic canary cage, personal items of workers on strike, as well as photos of activists like Mother Jones, Few Clothes Johnson, and Sid Hatfield. The collection probably paled in comparison to what remains on Blair Mountain, but it was very moving. I was given a generous personal tour by a woman named McCoy but with relatives from the Hatfield family. In front of a video loop of Sid Hatfield grinning, laughing, and spitting, she told me his story with affection and pride that was contagious.

Later, another guest at the bed and breakfast explained to me over breakfast that the plateaus left by mountaintop removal weren’t wasted; in many places they became housing developments, or shopping centers, or municipal airports. On my way home I traveled for a while along the King Coal Highway, a beautiful drive that traces the tops of the mountains, connecting several historic coal towns. In many places, sections of the mountain have been carved away to allow a straighter path, dramatically revealing underlying stratigraphy; layers of 300-million-year-old limestone and black bands—coal seams, I supposed. Along the highway is Mingo Central Comprehensive High School, replete with a large football stadium—home of the Miners—built on the remains of a leveled mountain. With Blair Mountain in the back of my mind, it was hard to make sense of all these strata, exhumed, flattened, the coal turned into fire and smoke and steel, with what remains undergirding homogenous housing complexes, a high school, an airport, a Walmart.

- – Nick Crockett, MFA ’19