In a career spanning more than four decades, photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris captured the events and everyday experience of African American life in Pittsburgh, leaving behind an archive of more than 80,000 photographic negatives. When the Carnegie Museum of Art (CMoA) acquired the trove of images in 2001, most came without names, dates, locations or other identifying information. Now, a new collaboration between CMU’s Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry and CMoA aims to identify, annotate, and organize visually distinctive features through the use of advanced machine learning and computer vision techniques.

The project, which was just awarded an NEH grant, arose from School of Art Professor Golan Levin’s undergraduate Interactive Art and Computational Design class. Zaria Howard, a School of Art junior pursuing a BHA degree in Art and Statistics, developed a keen interest in the archive and the complex problems of identifying individuals, locations, dates, and other visual elements across the vast collection. Professor Levin, who is also the Director for the STUDIO, is leading the project, along with David Newbury, Enterprise Software and Data Architect at J. Paul Getty Trust.

From the 1930s through the 1970s, Teenie Harris chronicled life in Pittsburgh’s black neighborhoods for the Pittsburgh Courier, one of America’s most influential black newspapers of the 20th century. At a time when African American communities were largely omitted from mainstream media, Harris’ images came to form one of the nation’s most important records of African American life during this era.

CMoA has been working to add metadata—identifying information such as names of individuals—to the digital images through interviews with contemporaries of Harris and, whenever possible, the original community members documented in his photographs. To date, about 2,000 images, or just 2% of the archive, have been positively identified. This process is incredibly laborious and time consuming. Furthermore, many of those who can best contribute this information are advanced in age, so time is of the essence. New tools are needed to cross-reference identified people, places, and events across the 80,000 images.

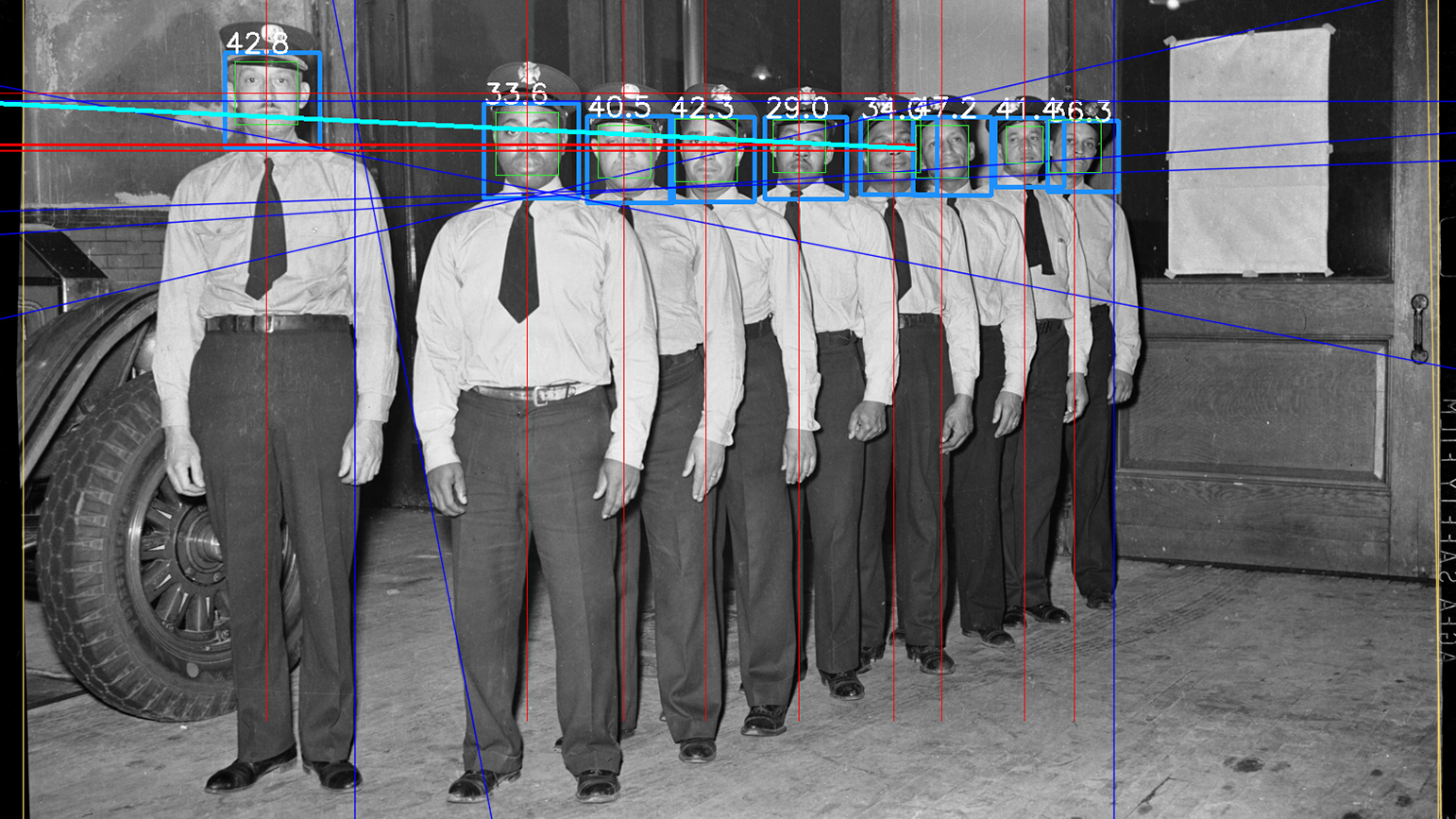

The new software will create machine-learning-based tools for image analysis and annotation. For example, the software will be able to identify specific individual faces that appear in different images throughout the archive. These potential matches could then be shown to interview subjects who could confirm whether or not the matches are correct. As a person interacts with the software, it will become “smarter” and better equipped to make more accurate matches. A similar protocol could be used to identify other objects, locations, or features in the photographs and add this metadata automatically to the images. This process would make the archive more easily searchable for both researchers and the general public.

Large troves of digital images that lack identifying information is not a problem unique to the Teenie Harris Archive: it is a problem that occurs in many cultural heritage collections. The software developed by the STUDIO will be open-source and compliant with international digital image standards, allowing the tool to be applied to collections across the globe.