“5 Questions” is an ongoing series with School of Art alumni who are transforming art, culture, and technology, exploring their creative practices, career milestones, and Carnegie Mellon memories.

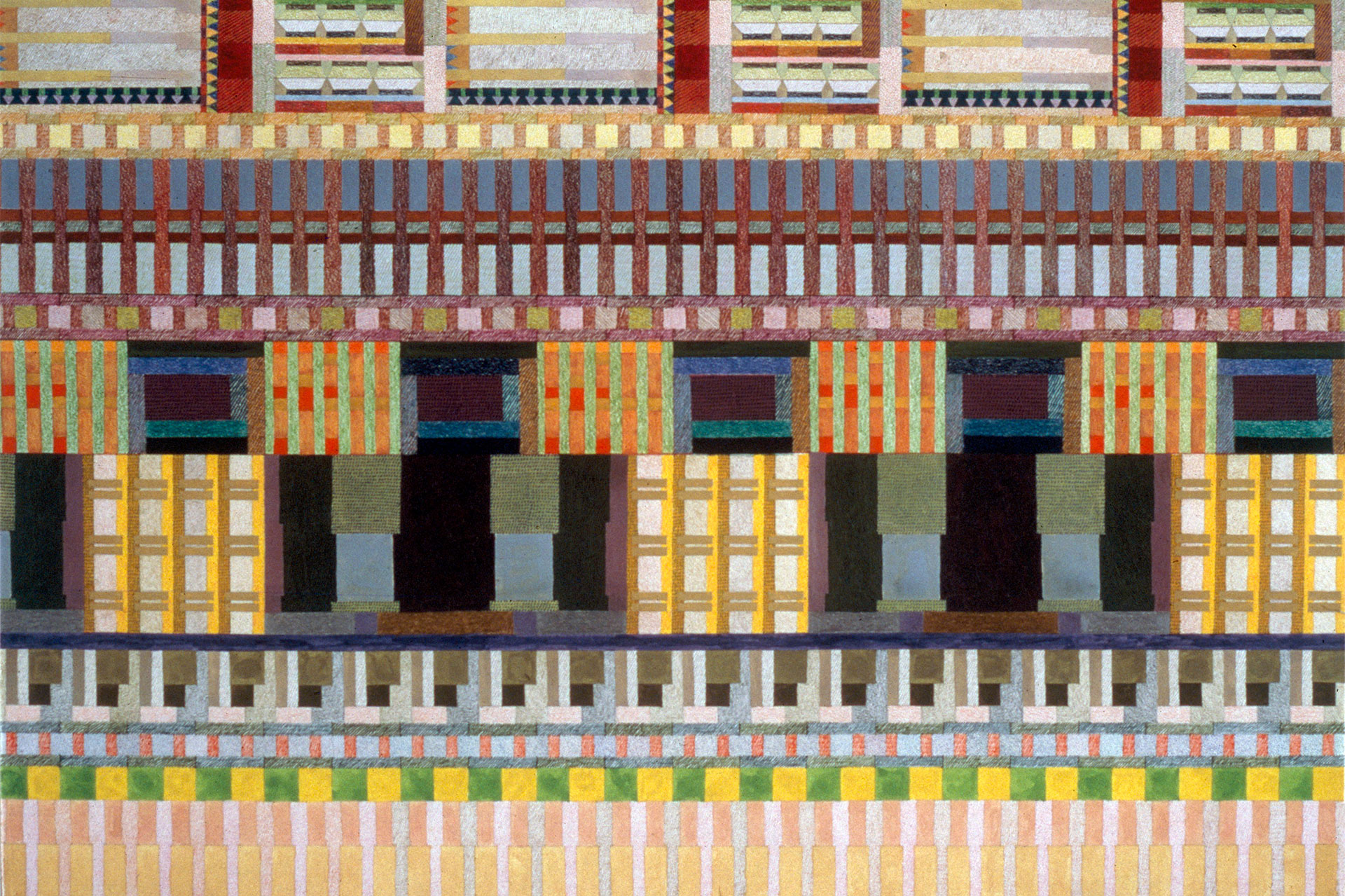

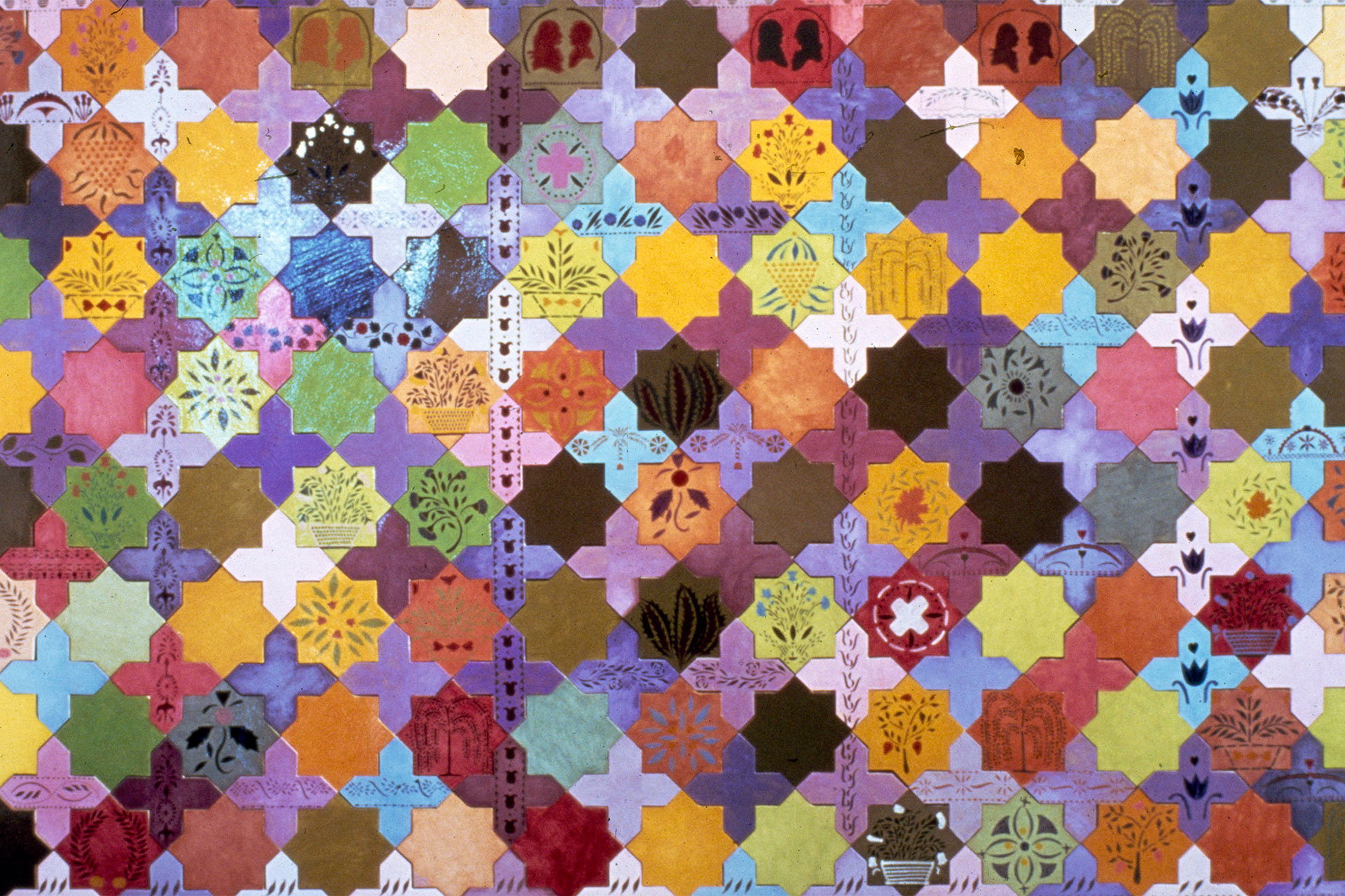

Joyce Kozloff has spent decades using art to challenge power structures. A key figure in the 1970s feminist art movement and a leading member of the Pattern and Decoration movement, Kozloff continues to push boundaries — most recently as a recipient of the 2024 Anonymous Was a Woman award. While known for her public commissions around the world, many executed in tile and mosaic, Kozloff’s ties to Pittsburgh also run deep. Her uncle, Jerome Rosenberg, was a longtime professor and dean at the University of Pittsburgh, while her aunt, Shoshana, was a freelance fashion illustrator. In this conversation, Kozloff reflects on her time at CMU, the influence of maps on her work, and the importance of maintaining an artistic community.

1

What drew you to cartography as a tool for exploring history, culture, and geopolitics?

It came out of doing public art. When you begin a public art project — it’s different now, but back then — you’d be sent a big stack of blueprints and diagrams of the building or site. I always thought of it as a kind of scaffold to weave my content into. For many years, I didn’t do as much studio private work because I was so busy with the public art. Toward the end of the last century, there were a lot of ideas I hadn’t gotten to, so I basically tried to finish the projects I had been working on and leave myself time to go back into the studio and work in a more intimate way. That was when I started thinking that maps could be the same way to work in my studio, that I could use maps as a structure to build other kinds of content into and onto. Maps are vehicles for talking about conflict, struggle, dominance, and power.

2

Do you see art-making as an act of political resistance?

I love making things, but I don’t really think I’m resisting when I’m when I’m making things. I’m very involved in beauty, but a lot of my work in this century has become much more political. I think the early work was equally political, but it doesn’t look today as political as it felt at the time. I was part of a group. We were really breaking barriers, and I certainly wasn’t the only one. The work I’ve been doing in the 21st century has a lot to do with war and conflict and trying to talk about that in my own visual language. I think that maps and patterns have certain things in common, in that they’re not high art, they are widely circulated and multi-purpose. I started making connections by looking very closely at maps of places, particularly places of conflict, and finding ways to weave information within the mapping.

3

How did your work come to focus on breaking down the high/low hierarchies of the art world?

I started thinking about breaking down the hierarchy between high art and craft through feminism, through the women’s movement, starting in 1970, really being immersed in groups of women artists who were looking at how we were left out of mainstream art history and why. It’s just part of me, it’s in my work, it’s in my conversations with people, and it’s in the other work that I look at.

4

Take us back to your time as a CMU student. What kind of work were you making?

In the beginning I was a graphic design major, but I wasn’t good at it, and I didn’t like it very much. The last two years, I switched to an Art Education major, and I student taught in Pittsburgh public schools, both elementary and high school. I took my studio courses, particularly painting at night, but the course that really changed my direction was called The Oakland Project taught by Robert Lepper. He taught that course every year to juniors, and every week you were supposed to go out into the streets of Oakland and document — photograph, draw, paint — and bring it back. Then we put them all over the walls with push pins and discuss what everyone was doing. I just totally got into that, and I couldn’t be in the streets enough. I’m a public artist, and I really think that’s where it began.

5

What advice would you offer art students now?

Same advice I’ve always offered: build a community, especially when you leave art school. I don’t see how anyone, particularly a young artist, can survive without it. Despite all the mythology about the great loner artists, it’s such a struggle, and there are so many disappointments. A support system really makes a difference. For me, it was through the Women’s Movement. I always feel very lucky that I came of age at that moment.

More from Joyce Kozloff | joycekozloff.net | @joycekozloff

Top: Photograph by Grace Roselli