Influenced by the techniques and strategies of American folk artists, Jina Valentine’s interdisciplinary practice examines pervasive social, political, and economic inequalities of contemporary American life. Her works confront issues such as police violence against Black people, how gerrymandering disenfranchises voters, and the financial incentives of policies, such as private prisons, that disproportionately affect Black and brown people.

Valentine is also the co-founder with Heather Hart of the Black Lunch Table (BLT), a project that brings attention to the lives and works of Black artists. Initiatives of the BLT include oral archiving, workshops, meetups, and Wikipedia edit-a-thons.

Valentine’s work has been exhibited at venues across the country including at The Drawing Center, The Studio Museum in Harlem, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. She received her MFA from Stanford University in 2009 and is currently an Associate Professor of Printmedia at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

“5 Questions” is an ongoing series by the School of Art that asks alumni who are transforming art, culture, and technology about their current work and time at Carnegie Mellon.

(10 in series) 14 x 20 inches irregular.

What role do you see your artwork playing in bringing attention to social and/or political issues, such as gerrymandering or police killings of Black people? How does this role differ from other mediums, such as news accounts or social media activism?

I don’t think of my work as activist per se, but I am interested in how it can catalyze conversation. For example, not everyone who sees my drawings of gerrymandered districts will immediately recognize them as such. It’s my hope that a series like Literacy Test: Rorschach will inspire people who don’t know the references to read up on history and politics.

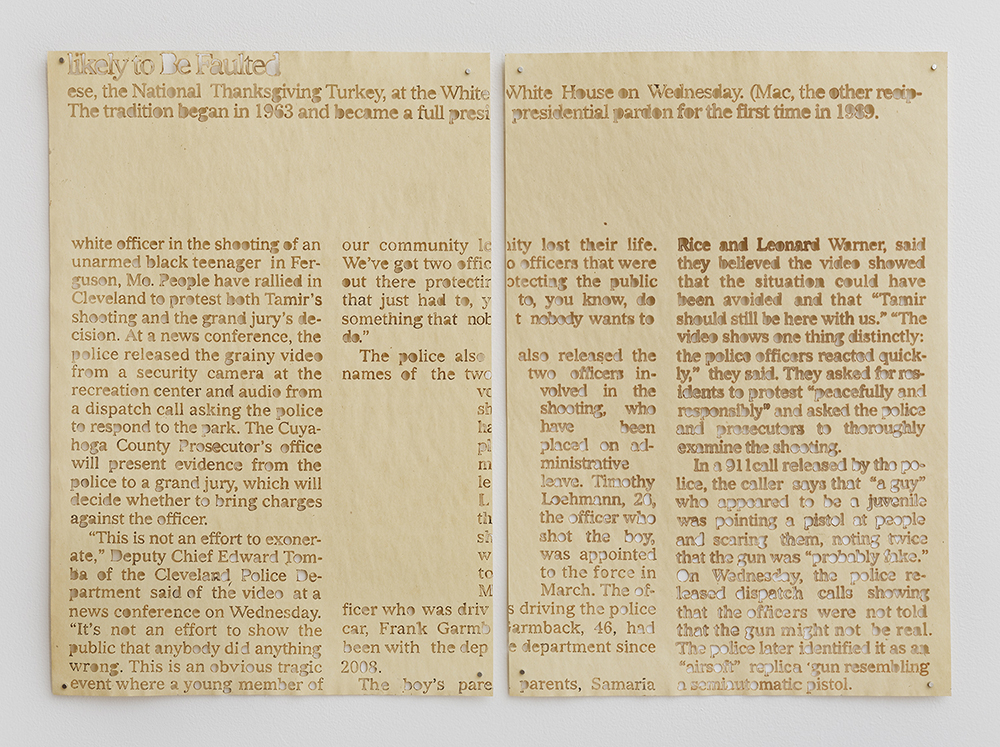

I taught a class at Oxbow called in | un | data : humanizing data viz, which was kind of borne out of my relationship with (big) data. The class intended to inspire students to consider their own relationships to data (collected about them, and presented to them) and how our lives are analyzed, mediated through data, and how data visualizations can oversimplify complex phenomena. The work that comes out of that class, and out of my studio infuses the visualization of data with a measure of humanity. Whether it’s about number of unarmed Black people killed by police, the effects of gerrymandering, or the relationship of for-profit detention centers to executive memoranda, my work intends to recontextualize sociopolitical and socioeconomic data, by bringing it closer to the lived experiences it intends to illustrate. I also like to compile illogical and incompatible datasets. I’m not a data scientist and like to take liberties with research.

Who uses the archives created by the Black Lunch Table’s conversations? Do you see interest from academics, other artists, the general public, or some of each?

The Black Lunch Table communities include: the artists and citizens offering testimony and contributing their lived histories; institutions who host our events; (art) historians interested in a particular movement, person, issue; students and researchers; curators seeking a deeper understanding of a particular artist, issue or location; friends, neighbors, and web users; all those parties collaborating in the writing of contemporary cultural history.

BLT addresses historical omissions by empowering the people to right the record. We are mobilizing a democratic rewriting of contemporary cultural history by animating discourse around and among the people living it. Recording, transcribing, archiving, and publishing their stories validates and amplifies their voices. And the integration of BLT archive materials into syllabi, research journals, Wikipedia entries, podcasts, radio stories, and popular discourse further authenticates them: they become part of our historical record. The BLT archive provides a unique collection of vernacular histories, presenting cultural history, inter/nationally, as it is recounted.

Are you hopeful that the statements and promises made by many art institutions following the police killing of George Floyd will result in meaningful and lasting change?

I am only cautiously hopeful that the anti racism pledges and statements of solidarity made by arts and academic institutions will catalyze significant and lasting change within those institutions. I am hopeful that the discourses made visible by this summer’s international protests have heightened many Americans’ awareness of how deeply embedded white supremacy is in our culture. It is hopeful that many of these petitions and letters came from young people, and from students. And in art institutions it has been awesome to witness undercompensated, underrecognized, precariously employed staff spearheading efforts towards fairer labor practices, employment equity, healthcare/sick leave, and demanding representation in institution-wide policy making.

As faculty at SAIC, it has felt purposeful and critical that we support our students and staff’s demands for more a equitable, diverse, inclusive, and just institution. As a Chicago-based artist, it has felt just as critical artists leverage our collective voices in support of art workers. Notable Chicagoland petitions from this year include:

@dismantlesaic, #saicsolidarity, SAIC_BlackFuturesLetter, MCAccountable, More Than Diversity at UChicago, and English Dept. at UChicago

These letters have sparked change, but the work is far from done.

Could you talk a bit about your time as an undergraduate at CMU’s School of Art? Are there any experiences you had as a student that stand out?

Wow. I could say a lot about my time as an undergraduate. Succinctly, though, I am really a product of my time there. I think back on the the folx in my cohort: Lauren Lamonica, Zak Prekop; Peter Burr, Mandradjieff, Coppin, and Coffin; Carrie Schneider; Bianca Beck. And the mentors I had/have: Satoru Takahashi, Susanne Slavick, Martin Prekop, Steve Kurtz… and although I just missed Ayanah Moor, our paths have aligned here at SAIC. Nearly twenty years since receiving my BFA (!!?) I still feel deeply connected to that place and time. My practice is very much concept + research based, is still very much interdisciplinary, and it exists in dialogue with those peers and mentors.

Do you have any advice to share with students?

CMU is a gem. It is singularly complex and weird and wonderful. While in undergrad I soaked up inspiration, information, resources… taking classes across departments, as well as at Pitt, Pittsburgh Filmmakers, and in study abroad. My advice is to trust the path you are on, including any detours and impasses. Keep in touch with your mentors, old friends, and yourself. Oh, and keep making art.