Though nearly all artists who pass through the School of Art at Carnegie Mellon University are influenced by its most famous alumnus, Andy Warhol, only one has commandeered his approach to appropriation to rewrite the patriarchal narrative of art history. Across a varied practice that includes painting, sculpture, drawing, and printmaking, Deborah Kass’s work asserts that she—along with other female artists, creators, and intellectuals—deserve a prominent place in our shared cultural history.

On November 4, CMU will honor Deborah Kass, who graduated from the School of Art in 1974, with the Alumni Achievement Award. Members of the public are invited to join the virtual awards ceremony by registering here.

Kass discovered her passion for artmaking at an early age. As a teenager, she took the train on Saturday mornings from Long Island to Manhattan to take classes at the Art Students League, spending afternoons at MoMA, the Met, or a Broadway matinée. Kass has said that although she fell in love with modernism at MoMA, she did not see anything in the galleries that reflected herself, as the work was almost exclusively by men and representations of women nearly always idealized.

When Kass enrolled at CMU in 1970, she found a wildly experimental atmosphere led by a crop of young faculty who were “super ambitious and super plugged into what was going on in the art world.” Characteristic of the hippie culture and ethos of art schools in the ’70s, Kass said her time at CMU was “four years of insanity” that came with a mandate to “expand our minds,” a directive she, and her peers, took very seriously.

After graduation, Kass moved to a loft in Tribeca during the height of the second wave of feminism. Here, she was immersed in an art world centered around SoHo that celebrated the work of women artists.

“It was a thrilling time to be a young woman painter,” she recalled. “Work by women was everywhere, and it was a time when women had enormous political power. When people wanted to know what women were doing in art, it meant painting and sculpture.” Prominent galleries such as Paula Cooper, OK Harris, and Holly Solomon showed work by artists such as Pat Steir, Mary Heilmann, Elizabeth Murray, Faith Ringgold, and many more.

The advent of the Reagan era ushered in a backlash against feminism along with a surge in money flowing into the high end of the art market, which consisted almost exclusively of male artists. Women artists during this time, especially those working in painting and sculpture, were forced from the center of artistic and cultural discourse. Still, Kass had her first solo exhibition, at the storied Baskerville and Watson gallery, in 1983.

Revisiting her experience as a teenager unable to find a representation of herself at MoMA, Kass began her series she named the Art History Paintings in the late 1980s. These works, which appropriate the work of iconic male artists including Picasso, Jasper Johns, and Jackson Pollock, question why there was no one like her in art history. Of her approach to appropriation, Kass cites Adrienne Rich’s quote “This is the oppressor’s language, yet I needed it to talk to you.” Through this language of appropriation, Kass’s works force us to consider why the contributions of male artists are highly valued, both commercially and culturally, while the work of female artists is often overlooked, ignored, or derided.

Following this series examining her absence, Kass next chose “to talk about my presence.” Again, she thought back to her time as a teenager and when she first saw herself reflected in culture. “It certainly wasn’t in MoMA, but it sure as hell was Barbara Streisand when she exploded on the scene.” Streisand looked radically different from the stars of the day, but her unwavering self-regard led her to stardom. “She was a Jewish girl from Brooklyn who wouldn’t get a nose job or change her name, and that she thought that much of herself,” Kass said. “That self-regard was feminism before I had any sense of feminism.”

Between 1992 and 2000, Kass began to use the language of Andy Warhol, and she featured Barbara Streisand in many of her works from “The Warhol Project.” In other pieces, Kass replaced Warhol’s pop culture celebrities with her own pantheon of heroines, including writer Gertrude Stein, artist Cindy Sherman, scholar Linda Nochlin, and choreographer Elizabeth Streb. This series created an alternate canon in which Warhol’s tragic muses are replaced with a celebration of female artistic, cultural, and intellectual achievement. “The Warhol Project” provided the backbone to Kass’s 2012 midcareer survey “Before and Happily Ever After” at The Andy Warhol Museum.

Kass next dedicated her practice to an examination of language and its intersection with politics, popular culture, and identity. In her series “feel good paintings for feel bad times,” Kass brought contemporary anxieties into focus by tapping into the nostalgia for earlier periods of American optimism, often through references to contemporary art history, Broadway musicals, and the Great American Songbook, among others.

From this series emerged what has become Kass’s most iconic work, “OY/YO.” Her first monumental sculpture, “OY/YO” has quickly become a powerful symbol for the intersection of cultures in New York City and the United States more broadly. Consisting of two gigantic canary yellow letters, the sculpture can be read as the Yiddish “oy” or as “yo,” referring to Brooklyn slang as well as the Spanish “I.” The sculpture, first installed in Brooklyn Bridge Park in 2015, is now installed at the Brooklyn Museum, and another version can be found at Stanford University’s Cantor Arts Center.

“I never expected to make a wildly popular work of art,” Kass said. “It’s remarkable having made something so accessible and beloved.” Kass, who has supported progressive causes for her entire life, said she was especially moved by photos of thousands gathered around her work in front of the Brooklyn Museum for the Black Trans Lives Matter Rally in the summer of 2020.

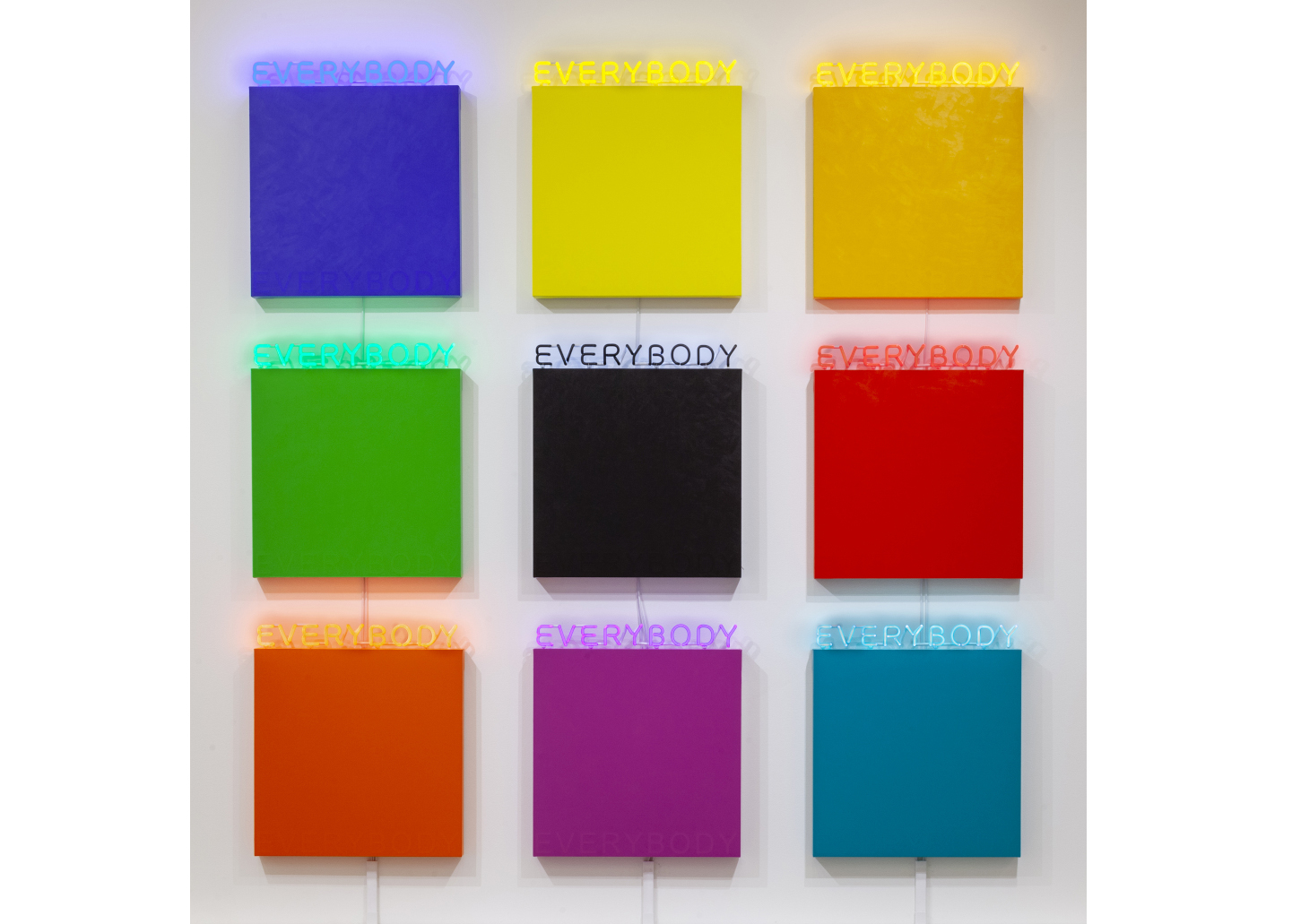

In her current work, Kass said she is working on iterations of her 2019 piece “Everybody,” which is influenced by the Martha Wash/Black Box song, “Everybody Everybody.” This recent work is focusing her attention on democracy “and what is art’s relationship to democracy and what do I think I could contribute to that,” a theme she said she’s been working with for a long time, though not framed in that manner.

“Deborah Kass’s work is at once bracingly witty and keenly critical, deeply personal and perfectly attuned to broader society,” said Head of School Charlie White. “Her work calls attention to the gross imbalance of power that sidelines the intellectual, artistic, and cultural contributions of women, and she makes room not only for herself, but for those who came before her and those who will come after. And as xenophobic rhetoric and division continue to challenge the foundation of American identity, Kass’s work reminds us of the power inherent in the intersecting of different cultures. I can think of no alum more deserving of CMU’s Alumni Achievement Award than Deborah Kass.”

Kass’s work is collected by many of the most important museums in the United States, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York; the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; and the Museum of Contemporary Art, San Diego.

Kass’s influence extends beyond museums through her service to art education and support for arts nonprofits. From 2005-12, she was appointed Senior Critic in Painting and Printmaking at the Yale School of Art. In addition, Kass currently sits on the Board of Directors for the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, one of the nation’s most important funders of visual arts, as well as for the Sharpe-Walentas Studio Program, an artist residency program that provides rent-free studio space for 17 artists in Brooklyn.

Nominations are now open for the 2022 Alumni Awards! Nominate an alum for next year’s awards here.