Dana Lok’s paintings reveal the magic within everyday experiences and within modes of communication. Both technically and thematically, her work conflates seemingly contradicting systems: flatness and depth, illusion and handmade, symbol and object, abstraction and representation, and more. Her work often combines multiple viewpoints, as well as multiple moments in time.

After graduating with a BFA from Carnegie Mellon, Lok earned an MFA from Columbia. She’s had solo exhibitions at galleries in New York City, Milan, and London, as well as at the Frieze Art Fair in New York.

“5 Questions” is an ongoing series by the School of Art that asks alumni who are transforming art, culture, and technology about their current work and time at Carnegie Mellon.

What makes a painting—a static, singular image—a good vehicle for investigating time in your work?

It’s a counter-intuitive aspect of a still image that it lends itself to picturing time. I address time in my paintings by showing temporal relationships as spatial relationships. That might look like a comic strip: one moment sits next to another on the left and right sides of a canvas. Or it might look like a peeling loaf, where moments of time are squashed next to each other like slices of bread. This spatial way of thinking about time leads me to questions like, what’s the character of the edge between one moment and the next? What kind of shape does a process make as it flows through time?

In film or performance, the artwork literally occurs through the medium of time. In the same way a fish might not notice the water it swims through, a viewer won’t notice the flow of time unless you introduce something like disruption in the current. I could imagine ways of doing that in time-based media, but it’s a different way of calling attention to process and temporality than metaphorically representing them.

Tell us about how your images are inspired by theater.

I’m interested in overlapping features of how paintings and theater work on a viewer. A painting traditionally offers you a controlled, singular viewpoint of a scene, like the front and center seats at the theater. I like to imagine the pictorial depth of a painting might extend over the whole depth of a stage and that parts of the painting are stacked like elements of a theater set. If that’s the case, a painting could offer you a sneak peek of the scene from the wings or from the orchestra.

A painting also uses compositional cues to direct your attention and your gaze, just like theater. The painter might be the sly magician, who uses misdirection to distract you from the mechanics of a trick. Of course, by going to the show, you’re willing to be tricked.

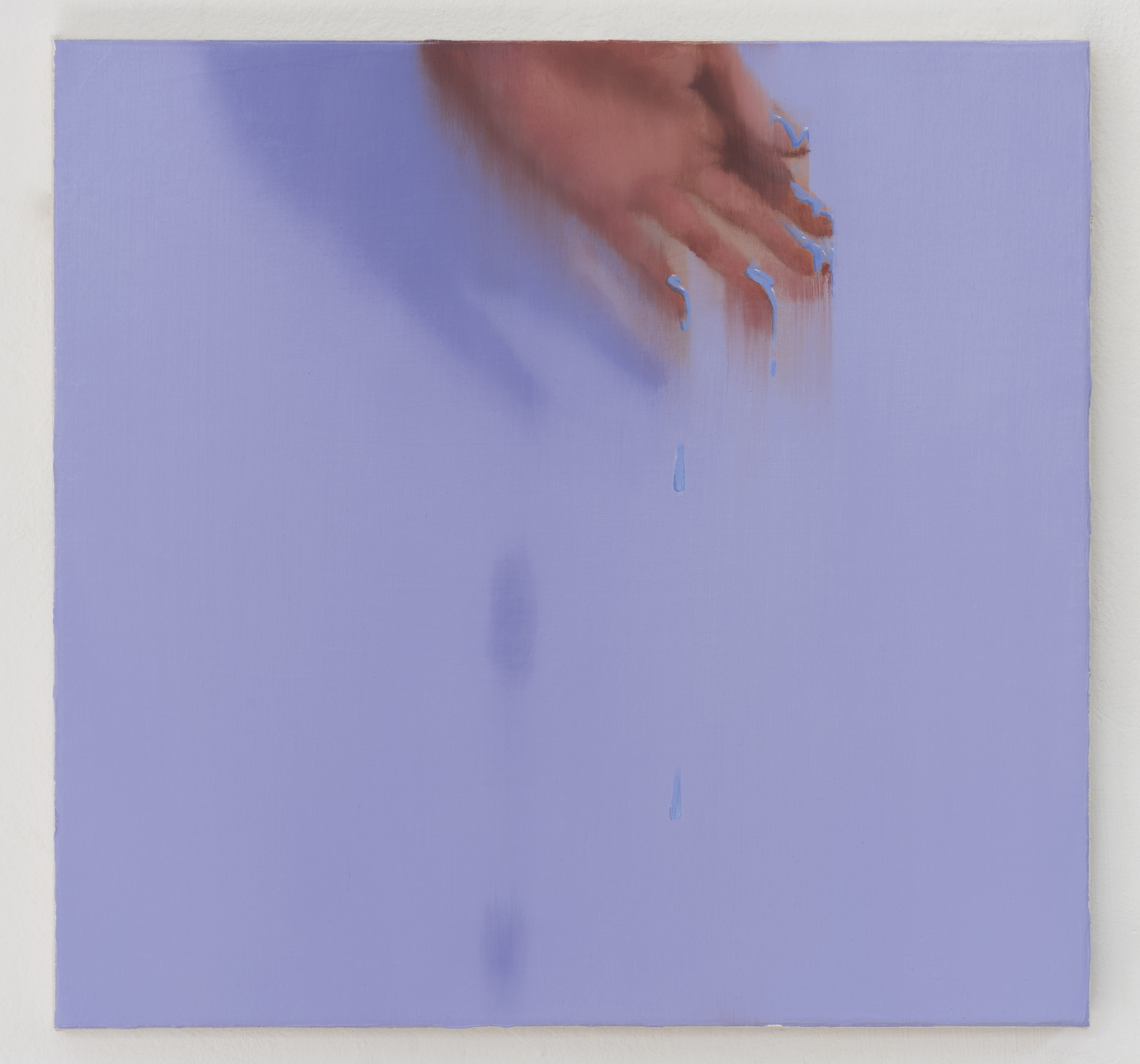

Much of your imagery is executed in a very precise manner, only to have a handprint or obvious smudge on the canvas. Why is it important for you to include these references to the hand?

Pointing, prodding, and smudging hands and fingers show up often in my work because I think a lot about how we represent and gain knowledge about the world. I’m invested in showing the process of gathering knowledge as tactile and sensorial. I like thinking about it as an act that requires physical contact between surfaces. That might mean a pointing finger turns into a poking finger. Sometimes I depict these hands as just another part of a painted scene. In that case, everything I can get out of the illusory capacities of oil paint, I use. But sometimes I like to show the actual evidence of a hand or finger on the surface of the painting itself. The actual impression, or index, of touch on the surface of the canvas introduces a whole second layer of representation, and that layer – if I can get it to work – adds dynamism to the painting.

Could you talk a bit about your time as an undergraduate at CMU’s School of Art? Are there any experiences you had as a student that stand out?

I was drawn to CMU by the conceptual emphasis of the program and encouragement to think across media, which still sets the program apart. After Susanne Slavick and Mary Widener’s energetic 2D foundational classes, things blossomed in my junior year when we got to work in our own studios. Professor Merrell’s Color class attuned my eyes forevermore to color effects I use all the time in my work, and Jacob Ciocci’s 2D animation class introduced me to moving image works I still return to for inspiration.

Coursework in philosophy fueled my project ideas all throughout school and initiated a really productive cycle of alternating between reading and image making. These days if I’m chasing down the inspiration to work, I still call up this memory of dropping my books, bags and coat in my senior studio cubicle at 10 in the morning after a philosophy class, exhausted from too little sleep, but with such a buzz, cup of coffee in hand, so excited to paint.

Do you have any advice to share with students?

These four quick years mark the period of time you get to develop the vocabulary, strategies, themes and the framework that you will use for the rest of your life in art. Soak in as much as you possibly can, as broadly as you can. With as many classes as Mark Cato let me cram into my schedule, I still think about this one philosophy course I dropped because the other kids seemed so much more on top of their game. I probably would have gotten a mediocre grade if I stayed put, but I would have learned something I’d really like to use today. Take the bad grade, take the risk, take the extra class! The end goal is to gain new experiences, not to achieve perfection.