“Others Who Struggle with Nature” features new work by Professor Lyndon Barrois Jr., and his first solo presentation in New York. Among shifts and changes in the artist’s practice, as well as relocation(s) and loss of materials due to the conditions of the pandemic, he has returned the context of sport and spectatorship, relative to branding, image production, individual identity, and collective behavior. The exhibition is on view at Rubber Factory beginning November 18.

It began with a National Geographic ad from 1989 advertising Goldstar as the media and technology sponsor of the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul. The ad was the seed reference for this project, and the start of Barrois Jr.’s interest in the 88’ Seoul Olympics, specifically. The games were an opportunity for many Korean companies—from technology to apparel—to exhibit their offerings to the world, and promote an image of progress and modernity, in attempts to dissolve a predominantly povertous reputation. The hosting of the games also allowed South Korea to establish diplomatic relations with otherwise adversarial governments, and considered by some to be the unofficial bookend of the Cold War.

The exhibition builds on a consistent interest in locating parallels and contradictions between the featured content and broader culture. While the Olympics has historically brough nations together under the guise of global unity, it is worth remembering that many of the events, while peaceful in their modern iterations, were designed to display militaristic skillsets, and wartime abilities. Likewise, there is a circular relationship between rifles, cameras and timepieces, which all depend on their assets as precision instruments that mark time and distance.

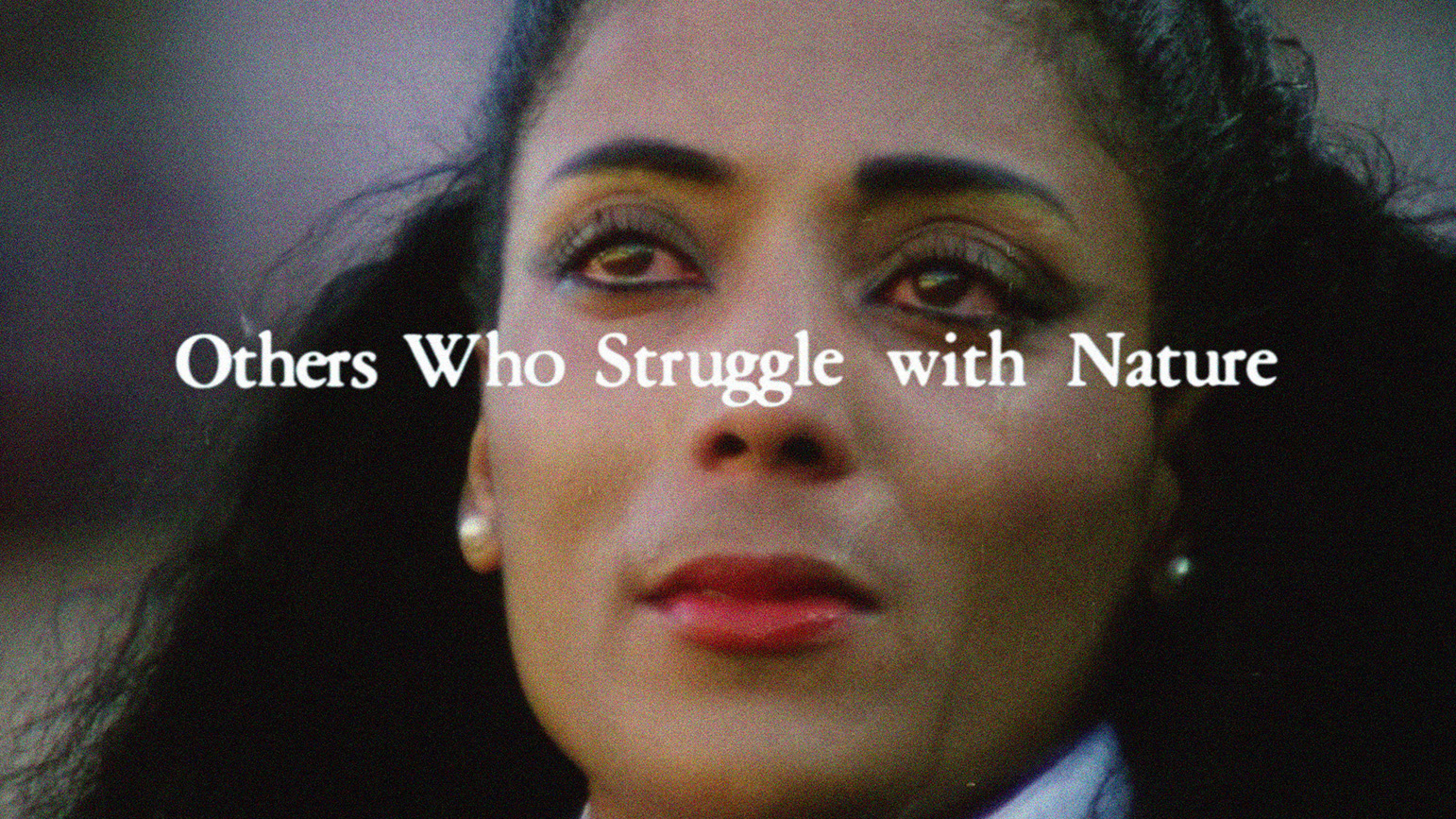

The title of the exhibition is taken from a title segment in the film “Hand in Hand” (Im Kwon-taek, 1989) following a segment on doping throughout the competitions. Those other athletes who ‘struggle with nature’ are ones opting to not cheat the process; ultimately physical competition is a war with the elements, our bodies, and the natural laws of physics. The phrase also opens up other questions around human nature, and the so-called ‘natural order of things’ in many social, commercial, and political contexts that we continue to struggle with in an evolving and re-volving manner with every generation.

Perhaps most recognizable is the likeness of Florence Griffith-Joyner, who won three gold medals and one silver in Seoul, setting Olympic and world records in the 100m and 200m sprint, respectively. The month prior, she set the world record for the 100m in Indianapolis, and these records still stand today. Often publicised for her fashion sense, it was reported that she spent more time each day on her nails and makeup than it took to complete the total 14 minutes of her event participation. Barrois Jr. is interested in this not as critique, but rather her recognizing the importance of image and self-presentation on a global stage. She also shattered the assumption that you cannot match fashion with exceptional performance. She has emerged as the only recurring figure throughout the exhibition.

The work shown consists of themed groupings and compositions forming relationships between collected film stills and ephemera from the event and time period. The three films being referenced are “Hand in Hand” (Im Kwon-taek), “Beyond Barriers” (Lee Ji-won), and “Seoul 1988” (Lee Kwang-Soo), all produced in 1989 to examine the games through different lenses. Each of these films present unique commentaries on the event, taking separate interests in particular sporting events, highlighting the spectacle of the opening and closing ceremonies, the political history of the Korean peninsula relative to other participating nations, and the militaristic undertones of Olympic competition. Barrois Jr. is intrigued by each of these perspectives, as well as the literal capturing of it all. At the heart of it all, there are many pictures of people taking pictures.