On the Ground is a series featuring research by graduate and undergraduate School of Art students at Carnegie Mellon University that offers a glimpse into the particular contexts, processes, and methods of inquiry that drive their work beyond the confines of the studio. This installment comes from Erin Mallea, a 2019 Masters of Fine Arts candidate whose interdisciplinary practice is rooted in a generative research process in which she observes, documents, inquires, listens, records, and collects.

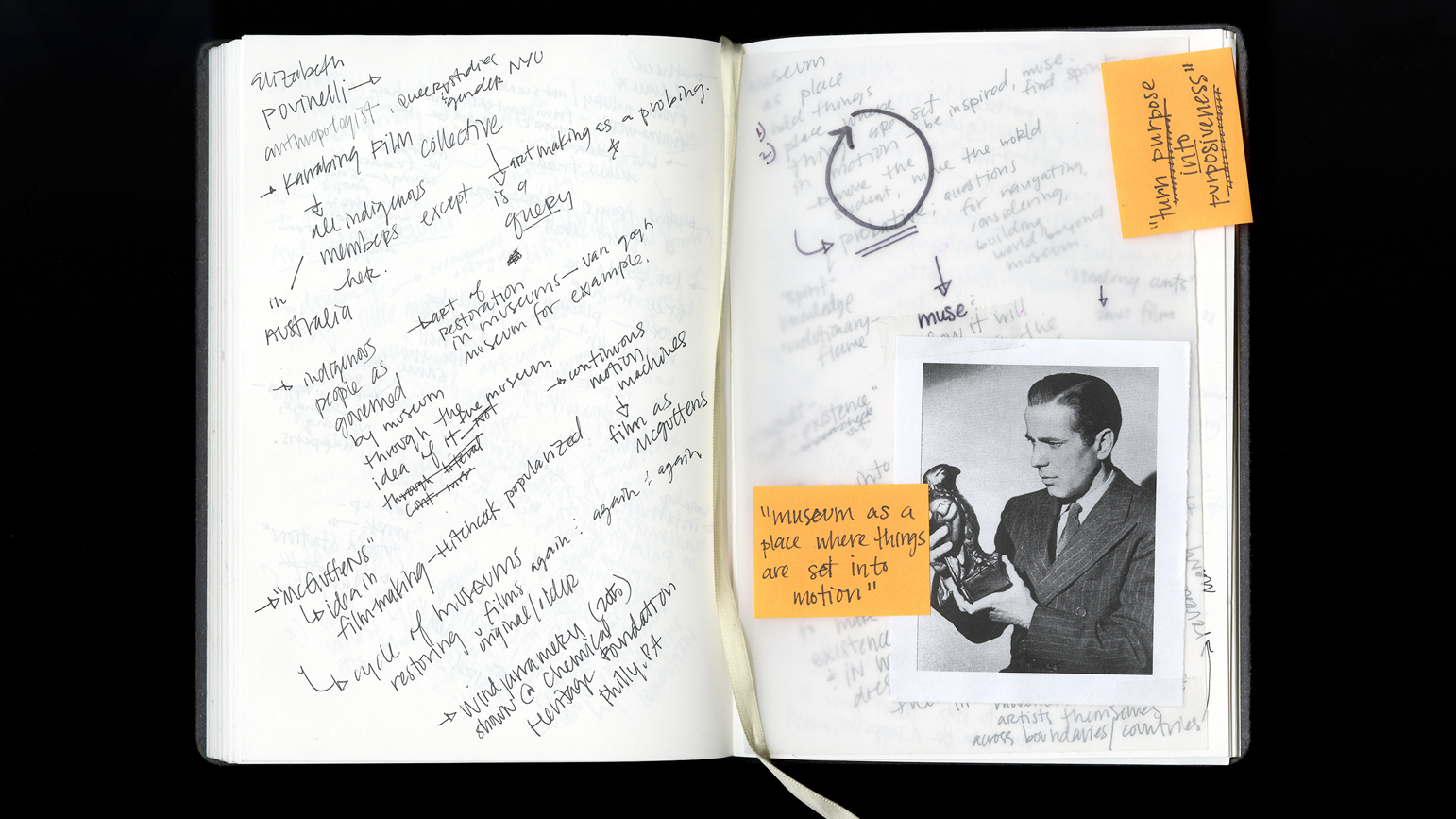

As part of my research, I traveled to Minneapolis in November 2016 to attend a symposium at the Walker Art Center. The conference, titled Avant Museology, focused on the practices and sociopolitical, philosophical, and ethical concerns presented by contemporary museology. The symposium considered contemporary art institutions in particular which have evolved to absorb, present, and collect their own complex histories and works of institutional critique that question the museum’s politics, past, efficacy, ethics, purpose, and structure. Avant Museology organizers asked, “can contemporary museology be invested with the energy of the visionary and political projects contained in the works that it circulates and remembers?”

The answer, according to two days of lectures and conversation was, not surprisingly, decidedly uncertain. While wary, some speakers remained hopeful. The symposium itself was cited as proof of the role museums can play as a platform for conversation, radical imagination, and probative questioning. The conference suggested that museums can be liminal thresholds: spaces that dissolve the status quo, call into question often unquestioned systems and hierarchies, and inspire individuals to actively make the world one wants to see. Many of the lectures remained exclusively in the intellectual and theoretical stratosphere, arguably resisting a more practical approach towards the commonly agreed upon problems. The few speakers that inspired a hopefulness about the museum, and by extension art, were those that grounded their ideas and practices in more tangible ways. This is not to suggest that theoretical or critical approaches towards museological discourse are unimportant. In fact just the opposite is true. When museums are a space for dialogue they succeed in embodying the ideas and ideals of the work they circulate. Nevertheless, during the two-day symposium that aimed to tackle these issues, the same nagging question continued to resurface in my mind, “What is theory without action?”

When considering the sociopolitical concerns presented by contemporary art institutions, it is essential to transcend the sphere of theory and investigate the world we are all physically implicated in and consider how such systems manifest in relationships to others, institutions, and global politics and markets. The conference confirmed the necessity of that nagging question. Elizabeth Povinelli’s lecture, “Filmmaking as Perpetual Motion Museum” was one of the few lectures that integrated theory and critical, real-world probing of systems of power. Povinelli is the Franz Boas Professor of Anthropology and Gender Studies at Columbia University. Povinelli discussed her work with the Karrabing Film Collective, a grassroots, Indigenous group and social project in the coastal region of northern Australia. The collective’s structure maintains the cultural ideals of their Indigenous community. The Karrabing are an intergenerational working group that rejects state forms of land tenure and group identification. Povinelli explained that the purpose of the collective’s filmmaking is not to produce an art object but rather to “make Indigenous existence work on and within a world that does not want them to exist.”

Povinelli utilized the concept of the “McGuffin”, popularized by Alfred Hitchcock, as a metaphor for the Karrabing’s methodology. A McGuffin is an object or motivator in film that serves as a trigger for the plot. For the film collective the “plot” is more than the narrative content. The action of making is a “probative analytic” for examining the structure of the world the Karrabing live in. The plot becomes the action of making and, by extension, the act of “working on and within the world”. The films are an empowering and lived form of agency that reveal the systems of power, crushing oppression, and the limitations of daily life Indigenous Australians face in the legacy of settler-colonialism. For example, Karrabing films have been screened throughout the world. International travel poses a considerable barrier to Indigenous peoples. Acquiring the necessary identification and visas costs a significant amount of time and money particularly for those in poverty. Further, because of language and cultural barriers, the Australian issuing agencies regularly misspell native names on visa or passport applications rendering the paperwork invalid and costing the applicant additional time and money to correct the mistakes. This is only a small example of the larger systemic oppression Indigenous communities face. However, it highlights prohibitive obstacles even after Karrabing films have been accepted and labeled valuable and valid by presenting art institutions.

Povinelli addressed her position of power as the only non-Indigenous member of the Karrabing, explicitly asking symposium goers to consider why she was the only individual speaking at the Walker. How accurate is it to call the group a “collective” if one member is in a position of much greater freedom, power, and economic and social status? While this poses a fundamental problem, Povinelli stressed that the Karrabing’s methodology is founded on maintaining an egalitarian dynamic of making. When asked where the Karrabing would want their films to live, collective member Natasha Bigfoot explained that she wants the artwork to end up on their land. This land is their museum, she said. It contains their history, the traditions of their ancestors, and their collective, cultural memory. Historically, Western museums have collected and objectified Indigenous and “other” bodies. Cultural objects were stolen and valued for their “exotic” aesthetic with little consideration of purpose and context. The Karrabing’s desire for their projects to ultimately be housed on their land is a rejection of this legacy. In their museum, the work would be conversation with hundreds of years of history and hundreds of years of continued marginalization and exploitation. Further, the artwork would be more than the preservation of the past in the present but a continuation of their lives.

Throughout the symposium, many of the conversations seemed precarious and ineffectual, not only because speakers were preaching to the already converted, but also because the discussion remained largely within the context of the museum. Criticism ricocheted off the walls and dissolved into the lecture hall. Those in attendance appeared to be art world usuals. Curators, artists, and critics that operate within one another’s circles mingled over coffee, fruit, and granola bars during scheduled breaks. Much of the institutional critique was absorbed by the institution called into question.

Povinelli’s discussion of the The Karrabing Film Collective, in contrast, was one of the few lectures that resisted this tendency. Native societies have long been objectified and governed through the idea of the museum. There are two forms of Indigenous existence in settler realism. First, Indigenous communities can exist as though they are in a museum: artifacts of the past to be rarified and studied. Or they are asked to become white and conform to the culture that has overtaken them. The Karrabing Film Collective is an act of resistance and survivance in wake of these options. The collective maintains its Indigenous identity and structure on its terms in face of systems that command its members to abandon their cultural identity and assimilate in order to survive. Karrabing films present voices and narratives within spaces that have subjugated and forgotten them, spaces that often deny their existence as contemporary cultures. Further, the act of filmmaking aims to challenge obstacles and set change in motion. Here lies hopefulness and potential for art and the museum. Just as the Karrabing’s films are McGuffins or queries that set things in motion, the museum can and should propel similar action. The museum can be a space where individuals find a muse, a “probative analytic” that poses questions and alternatives for navigating, considering, changing, and building the world beyond the museum’s walls.

Avant Museology was co-presented by the Walker Art Center, e-flux, and the University of Minnesota Press. More information about presenters and lectures is available on e-flux conversations. E-flux featured live coverage of symposium day one and two.

Erin Mallea utilizes contextual practice, photography, installation, drawing, and video as a type of field work that is both analytical and meandering. Through this methodology, Erin utilizes personal and local history as a starting point to examine larger systems of constructing meaning and value. A child of the Mountain West and a “fly-over” state, Erin is committed to exploring the complexities of place, notions of “landscape”, and how perceptions and imagery of these concepts are generated, commodified, and politicized. Her work often encompasses community interviews, conversation with local organizations, and collaboration with institutions. Erin has exhibited and produced educational programming nationally. She has used a picnic table beside a lake in the Mt. Hood National Forest as a collaborative artmaking space, submitted partnership proposals to Carnegie Mellon University Grounds and Facilities to no avail, and recently gave a presentation to the Allegheny County chapter of the “Colonial Dames of America” advocating for an update to one of their historical monuments and the ethical memorialization and representation of a local oak tree.